I modified this

story from an earlier version

published in a scientific journal, Cybernetics

and Human Knowing, in 2009. Cybernetics is the

study of how complex systems use information to

regulate themselves. Here I portray sculpting in

that light, somewhat enlarged and

more fully illustrated

than before.

The linguistic challenges

of describing what paintings, drawings,

and photographs can illustrate inspired the

saying that “a picture is worth a thousand words”.

In scarcely more words than that, I will describe

what it is like to create 3D sculptural forms in

stone by movements of my body, mediated

by the tools of that trade and

informed in several

ways.

I discuss

only a few issues here,

each of them pointing to the

cybernetic nature of sculpting as a

human activity. Given that objective, I

emphasize the actions through which

sculptures evolve, and not just the

static “statues” them-

selves.

Sculptures are

the frozen endpoints of long,

complex generative processes, and

we need to think about how

they come to be.

Some component

actions are well-understood physical

and physiological mechanisms. How muscles

and tools work. Physical qualities of

stone. Safety factors, and

so on.

Other components,

like artistic imagination and

creativity, are far from understood.

Yet we must recognize their importance

and imagine how they function in

sculpting as a whole.

♦

♦♦♦

Perceiving Form

An effective aid to

visualization of 3D form is to run

your fingers over the surfaces of sculptures.

Gently and sensitively, everywhere and

in all directions, touching with

your eyes closed.

Cumulatively,

that builds correctly scaled forms

into your body, mind, and imagination.

That also happens during sculpting, and

the size and shape of the stone changes

constantly. Even imagining

touching sculptures in this

way does that.

Form is the

locus of contact

with stone.

Listening to the Wind

is 45 inches tall. I carved it in

banded green sedimentary mudstone. It

rests in a lovely green garden bower in all

seasons and all kinds of weather.

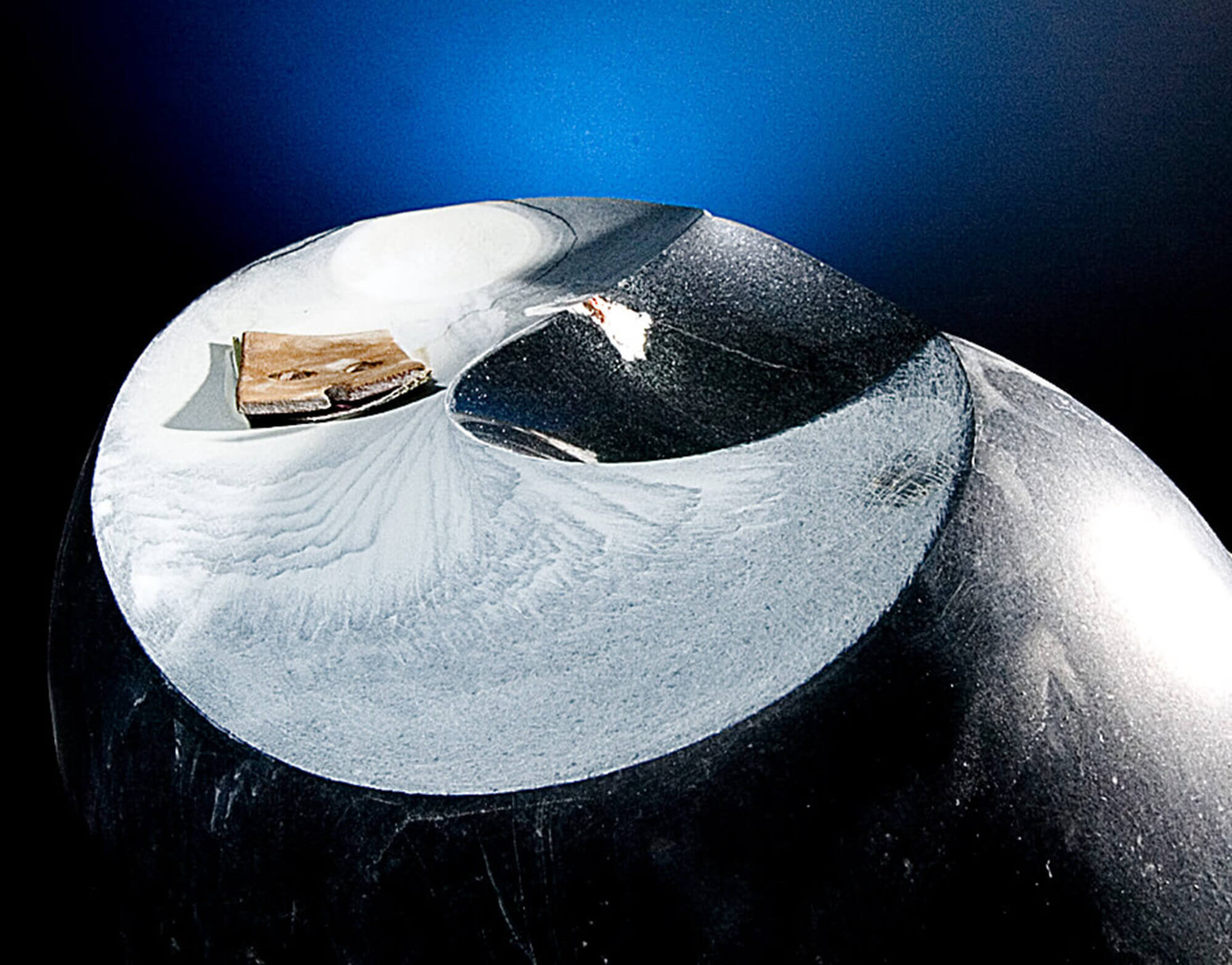

Heart of Anima

is a smaller indoor sculpture

of igneous basalt, 19

inches high.

♦

♦♦♦

Sculpting Stone

Consider

the whole, integrated

phenomenon of sculpting

those stones.

To begin,

think of them simply as

stones, each having evolved

through natural erosive action, much

as other stones do, then through

the active, intentional agency

of a human body and

mind.

Independently

of what these stones may

remind you of, or what you think

they may represent to the sculptor, regard

them simply as forms, and imagine how

the action of carving them might

have unfolded.

In that light,

notice a similarity between

these particular sculptures. In both

finished forms, surfaces swoop smoothly

through space, and intersections between

them are similarly-swooping curves

that hold the surfaces in place

in perception.

Another similarity is

that the slightly earlier versions,

lighted only by fields of laser light, are

not yet smooth at the finest scales. Over broad

regions of gently changing form, they are al-

ready smooth. But at the far finer scale of

surface texture, they are still rough,

complex, and chaotic.

If you examine the

images closely, you will

discover some of that roughness

as local irregularities in the

curvature of the

laser lines.

When I first

encountered those stones

they were boulders. Now they

are works of art. What happened?

What processes unfolded

during their evo-

lution?

I will address

this question indirectly, by

describing what it is like to use two

very different methods of shaping stone.

By the definition of subtractive sculpting,

both methods are destructive. They make

rocks smaller by removing parts of them,

and that is the fundamental operation

in carving stone, wood, or

soap, regardless of the

technology.

One method

disrupts the crystalline

structure of the stone, crumbling

it violently into sand, dust, and gravel.

The other rubs it away slowly, gently,

even sensuously, and removes

only dust particles

or mud.

Sensuality

and its close cousin eroticism

depend on meanings we find in

forms, and on actions through which

we form them. In that sense, we can say

that those meanings guide the actions

that produce the forms. We can

also say that the actions

produce meanings.

They

reinforce each other,

iteratively and recursively,

during the work. Here I

just want you to

imagine the

actions.

♦

♦♦♦

Percussion

Utility companies

use jackhammers to break up

roadways and sidewalks. Sculptors’

pneumatic hammers are smaller

and carve stone, but basically

they are the same.

Hammers come in

a range of sizes, remove less

stone in each cycle of action than

jackhammers, and afford far

more control of the tool.

Compressed air sends

a piston forcefully forward. It

strikes a metal chisel held loosely in

the snout of the hammer, the chisel leaps

forward, collides with the stone, and

bounces back to contact the

piston, several times

a second.

A bushing tool is

one of many types of chisels. It

presents 4, 9, 16, or more sharp, pyramidal

points of tungsten carbide to the stone with each

strike, carrying the momentum of the metal

tool and leaving up to that

many craters.

A tool bounces

violently against a surface,

pointed straight in, rotating freely

about its axis. Collisions knock the high

parts down, pushing the surface inward,

toward simplicity and integration in

the cases we will consider here.

A heavy bushing

tool in a big pneumatic hammer, used

with much air at high pressure, can degrade

granite quickly but without much precision. It

can also jar the body that guides it and cause

unplanned fractures in the stone, so it

pays to use it sensitively.

To give you a

sense of the destructive

power of these tools, that big

4-point bushing tool in the picture

is about 2 cm square at the face. It

concentrates a lot of force onto

those four points, and the

hammer kicks like

a horse.

At the other end

of the spectrum, tiny, many-

pointed bushing tools in tiny hammers,

used with little air, lightly frost nearly

finished surfaces. Used gently

enough, they do almost

nothing to the

form.

How

can such

violent methods

generate such gentle forms?

When used to accomplish

what I call integrating or resolving

form, bushing tools pound down parts that

are “high”, relative to ideal, imaginary surfaces

that lie beneath the surface, and don’t touch those

that are “low”. In subtractive sculpting, getting

rid of low places means pounding every-

thing else down to that level,

which is a drag and a

bother!

How anyone can

imagine forms like these, sometimes

wholly without specific reference to objects

in the real world, is beyond our scope here. It

is also beyond my understanding, though

I have experienced it every day of

my life and so have you.

However we do

it, “seeing” differences

between real and imaginary

surfaces identifies high places

and tells sculptors what

to take away.

♦

♦♦♦

Aids to Visualization

of Form

Rembrandt used

strong directional lighting

in paintings, chiaroscuro, to emphasize

the orientation and curvature of surfaces

and illustrate texture. That kind of lighting

is a common aid for artists, wild

animals, and other beings.

Brancusi’s

sculptures for the blind

remind us of the power of fingertips

to make the shapes of the world real for

us. His insights into the power of reflections

from highly integrated, highly reflective

surfaces to expand the perceptual

and emotional sizes of sculpt-

ures are profound.

The structured laser lighting

illustrated just below is a sensitive diag-

nostic tool. It reveals form especially effectively

when objects rotate in the light, when the

light scans across them, or when obser-

vers move relative to the forms

and to the sources of

light.

In those first figures,

Listening to the Wind and

Heart of Anima are nearly finished.

But close inspection of the images

reveals remaining irregu-

larities in both pieces.

In this detail of

Listening to the Wind, you

see a small set of grooves left by

a rasp. Once identified as a local

roughness by that and other

methods, it was easy to

remove.

Tools as

Probes for Information

Pneumatic hammers

are not just agents of erosion,

but rich sources of at least three kinds

of information about form. Each of

them is invaluable to sculptors

as they work.

This is

the essence of

cybernetics.

First, by maintaining

a constant average distance between a

sculptor’s body and a stone, pneumatic hammers

function as compressible sensory appendages.

They are sensitive probes that “measure”

surfaces, mapping them out in

sculptors’ minds.

Pneumatic hammers

are two-handed implements that

take many muscle groups to control. These

remembered patterns of contact between tool and

stone engage sculptors’ entire bodies and minds.

All of this happens as surfaces recede,

changing shape under the

rain of blows.

Second, as long as

the bushing tool strikes normal

to the surface and the surface is flat,

all points strike simultaneously, produce

equal craters, and the tool bounces

straight back into the

hammer.

{}

A surface normal

at any point on a surface is a vector

perpendicular to the tangent plane at that point.

Always, it is directed “straight in” or “straight out”.

Sets of normals representing entire surfaces

as arrows pointing in or out are called

vector fields of normals.

{}

Otherwise, only

some points strike the stone.

They make fewer, deeper craters,

and the process sounds and

feels quite different.

Attending to

sensations like these informs

slight adjustments of angle in real time,

maintaining the relationship between the

tool and the stone and keeping the

work going in a sensitively

controlled way.

And, because the tool

must keep moving over the surface of

the stone to keep it from digging in, its shifting

position and orientation are sensitive measures of

variation in the curvature of the surface. That

engages the entire body in sensing,

mapping, and changing

the form in real

time.

A third source

of information follows from the

fact that normals and tangents are per-

pendicular at every point. Those measures

are interconvertible mathematically, but

they mean different things to sculptors

and we experience them

differently.

A vector field of

normals is the set of directions

from which we “push” stone surfaces

inward. A field of tangents, fused into

a dynamically changing sense of form, is

a perceptual tension that unifies dif-

ferent parts of surfaces and

resists the pushing.

Given the richness

and immediacy of these bodily-felt

images, the details of carving collapse

experientially into unbroken series

of actions that “push” surfaces

inward to meet their

ideals.

We don’t need

to think about any of

that to do it.

♦

♦♦♦

Abrasion

Abrasion happens when

hard, rough materials slide over softer

ones under inward, normally-directed pressure.

The harder and sharper the abrasive and the greater

the pressure, the deeper the scratches it leaves. The

faster it moves, the more stone it removes

and the more quickly the

work proceeds.

Anyone who has

sanded furniture is aware of the

effort of scratching away hard material with

rough pieces of paper, and may have experienced

the wasted effort of using fine abrasives to

impart a polish before removing

coarse scratches.

Abrasives of

appropriate stiffness bridge across

low places and plane away the high, averaging

out local variation in topography and integrating whole

surfaces into unified perceptual wholes. This planing away

of promontories is an automatic result of stiffness that

requires no conscious thought other than to

select an appropriate backing.

The principle is

the same with curved stone as

with flat wood: to remove coarse scratches

by making successively finer ones until they

disappear, then possibly continuing to

the limits of the technology.

The harder the

parent material, the finer the

scratches it can hold and the higher

the polish it can take.

The finest scratches in

my polished Heart of Anima sculpture,

in basalt, are less than a thousandth the width of

the coarsest ones through which I did the final

shaping – – they are much finer than can

be seen without magnification.

If a surface

is ready for it, each succeeding

stage of abrasion takes less time and

effort than the one before, but it takes

inordinately more effort if the

surface is not ready.

I spent at least three

full weeks sanding Heart of Anima

at the coarsest stages of abrasion, when

I was still shaping, and less than a day

at the finest stage when I was

only polishing.

Crafting forms like these

by hand-powered, hand-directed

abrasion requires sculptors to “move” the

forms they create into being, as if dancing with

figments of their own imagination. Since abrasives

slide over surfaces, this would be a trivial insight

if the objective were just to smooth surfaces,

but it is not. The objective is to

change their shapes.

This means removing

more material from some places

than others. In turn, it means

modulating the process.

The relevant

variables, given the nature of the

abrasive and the stone, are velocity and

pressure at any moment and frequency of

abrading any portion of surface. Each

of those variables can be varied

continuously by

sculptors.

Those factors

determine how fast abrasion

removes stone, but consider the pattern

of action that removes it. As with percussion,

abrading stone is rich with information about

form. In both cases, using that infor-

mation makes the action

cybernetic.

As with percussion,

three kinds of information

are especially important.

First,

“rubbing on rocks”

with sandpaper affords a direct,

bodily-felt sense of form. This is the

integrated locus of contact. This is exactly

what happens with bushing tools, but

from closer contact and much

more precisely.

Doing this

engages entire bodies, minds,

and imaginations in several ways.

I often lose conscious awareness

of anything but the

action.

Sometimes, even the

stone disappears from view and

only form and movement exist

for me. That experience

is sublime.

Sculptors

performing the unbroken

series of acts of sculpting feel curvature

during each and every stroke. They feel it as

patterns of velocities and accelerations of

their fingers, hands, arms, and other

body parts, in relation to each

other and to the stone.

Humans and

many other species are acutely

sensitive to kinesthetic measures like these.

It’s how we keep our balance when we walk,

how we grasp, hit the ball when we swing,

and get our forks in our mouths instead

our lips. It affects how animals fare

in encounters, whether they

are predators or prey.

Listening

to our bodies speak to us

in that way while we work helps

us discover and correct irregularities

of curvature that are invisible

under all but the best

illumination.

♦

♦♦♦

Synthesis

During the week of my

40th birthday, in late February 1982, I

made a commitment: to behave as if sculpting

were my life’s work. I was fully occupied in research

at the time, and my work in education had not yet

begun to peak. Starting then, I applied the same

sense of purpose in sculpting as well, and

that made all the difference.

What did

doing that entail?

For one thing,

committing to work at sculpting

and not just play with it committed me to reflect

more mindfully on my own sculpting practice.

That helped me see sculpting as a complex,

interconnected, cybernetic system worthy

of my interest in its own right, just

because it is so interesting.

It also helped

me sculpt more

effectively.

Becoming more aware and

mindful made me even more aware,

recursively. It helped me experience sculpting

more vividly, and with a greater sense of

presence than before. Being more

mindful itself made the

sculpting better.

Since the very

moment of that commitment, I’ve

been intensely aware of the process of sculpting,

while I sculpt. I reflect often on the complexity,

the connectivity, and the multidimension-

ality among the component processes

of sculpting, whether or not I am

sculpting at the moment.

Gradually, I

learned literally to “feel” how

the work was going. Particularly

important was to learn to feel connections

between my ongoing physical and

mental experience and what

that does to the stone.

Driven by

the power of commitment,

sculpting is now part of me;

it is of my bones and

in my bones.

Humberto Maturana for the

perspective I take here, most of it gained

in workshops and personal conversations over

a 25-year period. Though I read what he wrote,

his most important influence on my thinking

was always through relationships

between his spoken word and

his body language.

He was a

great storyteller.

emphasis on the physicality

of sculpting here, it seems especially

appropriate that Maturana’s ideas

have perturb my understanding

in such physical

ways.

In the published

version of this article, I

thanked journal editor Pille Bunnell

for inviting me to be the featured artist

for an issue of Cybernetics and Human Knowing,

and to write the article. She also allowed me

to write in more experiential than scholarly

voice and to not worry about the

cybernetic literature.

At the same time,

she was also an inordinately

valuable coach on the language and

concepts of cybernetics. And as she

had been for me before, she was

a brilliant editor.

I still thank Pille

for all those things.

Edited August 2022