In late

August 1967, I was a brand-new

high school biology teacher in the suburbs

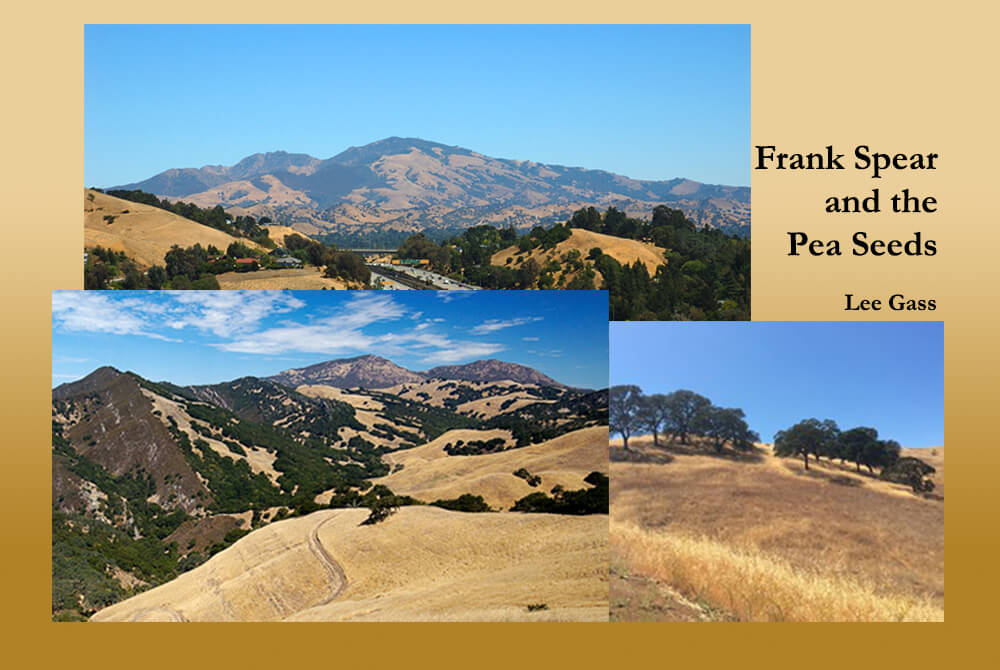

of San Francisco, east of Berkeley in Concord. That

part of California, and most of the state, actually, has a

Mediterranean climate. Cool, wet winters alternate with

hot, dry summers. No rain falls from April to September,

and between that and the heat, the grass and herbs

that make that part of the world so green in winter

and spring are dead by May and the hills

stand golden all summer long:

Golden California.

I hear spring can come overnight

in Michigan, Minnesota, and Manitoba,

and sometimes I try to imagine it.

Seasons

don’t snap into place

like that in California, and they

don’t slide smoothly from one

to the next, either.

Storms build up

and storms die back in

fits and starts.

First thing each

fall is a spitty little rainstorm

that hardly gets the windshield wet.

Then it dries back out and it gets

hot again, all in one day. It

might not rain again

for weeks.

Storms get

longer and wetter and fair

weather cooler and shorter till everyone

knows it is cool and wet, and winter. It is as

green as Ireland by New Year and as green

as the Shire by March. Then it dries

back up again and dies.

That first

autumn, I noticed something

wonderful. One morning on the way to

work, a couple of days after a little rainstorm, the

golden slopes of Mt. Diablo were tinged subtly with the

lightest shade of green, just a tinge and almost so faint

I couldn’t see it. A day or two later it was gone and the

mountain was golden again. The same thing happened

after the next storm and the next and the next, til dry

spells were cool and short enough and wet spells

long and wet enough for the world to look

and feel like winter. I wondered

about that often for a year.

The golden parts

of the mountain were annual

grasses and herbs that die every year,

so the green couldn’t have been

them “greening up”.

They died months

earlier and only their seeds remained,

I thought, so what could the greenings be

but seeds germinating after

each rainstorms?

If hills turned

green from germination

and then turned gold again, plants that

germinated early must have died before they really

got started. Only seeds that germinate late enough

in autumn would survive to reproduce. But which

seeds germinated early and died and

which were late enough

to live?

Every

time it rained next

fall, on the best day to do it, I took

my classes outside to the parking lot and

asked them to look up at Mt. Diablo. About

140 high school kids looked at one mountain

on several occasions approaching winter.

Each time, I asked the same question:

do you notice anything different

about Mt. Diablo today?

Nobody noticed

anything after the first

storm. We went back inside

with no discussion and

rumors circulated

about my

sanity.

After the

next storm, a few kids

noticed a subtle shift in color,

but it wasn’t dramatic enough

to capture their imagination.

It was

a start, though, and

we went outside again each

day to check the color. They

noticed the hills turning gold again,

but few 10th graders found any-

thing there to wonder about.

I managed

to lead them to realize

that the green must come from

seeds germinating and talked a

few kids into a bicycle expedition

into the hills to check that

assumption.

Their notes,

sketches, and collections

of dried-up seedlings confirmed my

suspicions about the biology. But I didn’t

know enough about stimulating creative

thought to take it much farther with

students without flat-out telling

them what I thought.

I learned mountains

about teenagers’ knowledge of the

natural world, and about their reasoning

power. But not enough about how they imagine

things to lead them to ask and answer

questions like that by

themselves.

Fortunately

for both of us, Frank

Spear solved my problem

and showed me how

it’s done.

In addition to

three 10th grade courses, I

also taught two sections of a second

year biology course for science ‘keeners’ who

had taken biology in 10th grade and had already

taken or were concurrently taking upper level math,

chemistry, and physics and mine was entirely a research

course after the first few weeks. This story describes

one of those investigations and Teaching for

Creativity in Science describes another.

Most of those

older students were no

more interested in the colour of Mt.

Diablo than younger students were, and though

they appreciated the tooth-and-claw meat of

who lived or died, they got little farther in their

thinking about the greening of the mountain

than the 10th graders. I found that both

fascinating and challenging.

One morning

a day or two after a minor

storm, Frank Spear came to see me

before class. He asked to take a chair to

the roof to sit and think about Mt. Diablo.

After cautioning him not to break his neck

or disturb the physics class that would be

below him, I gave Frank permission to

spend his class time on the roof, and

the same thing happened all week.

The next time Frank came to

class he confronted

me.

“I know which

seeds germinate after it rains!”

I asked what he thought and he replied,

confidently, that it was the little ones. Only the

smallest seeds get enough water to germinate after

little storms. Big seeds soak up a little bit, but not enough

to germinate. It takes more water because they’re bigger.

That lets big seeds dry up again until it rains enough

to let them soak up enough water. The little

ones already germinated and died.

The little seeds die

and the big seeds live. I thought

that was wonderful, and the first thing I did

was congratulate him. “That’s a fantastic idea”,

I said, “but what makes you so sure it’s right?” “Well

it makes sense, doesn’t it?” “Sure it makes sense, Frank.

It makes a lot of sense and maybe it’s right, but making

sense doesn’t make it right. Besides, you haven’t told

me what makes you think small seeds get enough

water and big ones don’t. What’s

so special about size?”

Frank didn’t

appreciate my conservatism

but he kept working on his argument,

and presented more and more of it each

day. Each day I acknowledged his progress,

then pointed out problems that still made

it difficult for me to fully accept his

story. Or believe it.

Gradually,

day by day and with

a great deal of frustration on

Frank’s part at my stubbornness but

nothing but delight on mine, Frank Spear

discovered for himself what he needed to include

for me to give in, cry uncle, and congratulate him

on a job well done and done. It took a lot, and the key

was for him to realize that the relationship between

the surface area and volume of anything, regardless

of shape, depends on its size. Based on that insight,

Frank eventually produced a formal version

of his hypothesis that he could and did

test experimentally. It took

him a while.

As we went

along, I freely acknowledged

the elegance, the completeness, and the

generality of Frank’s argument and praised

him liberally for each of his accomplishments.

I was very proud of him and let him know it.

But as impressive as his argument became

I made sure he knew it didn’t convince

me and wouldn’t convince

me until it did.

Rather than

explaining differences between

deductive and inductive reasoning

and getting him to test his hypothesis

experimentally, I just worried aloud

about his argument and let him

figure it out. Not surprisingly,

that frustrated Frank

even more.

Each day

in class he either sat by

himself, apparently brooding, or

asked to go to the library. His knowledge

of seeds, weather, geography, membranes,

germination, and soils expanded enormously

but Frank stayed frustrated that I wouldn’t admit

his formal argument solved the problem he had

started with. One day, Frank came to see me

before school started. “What are you doing

during your prep period?'” “I don’t know

yet, Frank, but I think I’ll be doing

something with you. What

do you need?”

“I want

you to take me to the

garden store to buy some pea seeds.

I need round peas too, not those wrinkled

ones Mendel studied. If I use wrinkled seeds I

can’t estimate their surface area and you’ll say

my experiment doesn’t answer my question. To

see whether small seeds germinate faster than

big ones my seeds all have to be the same

shape, right? If I use all round seeds I

can calculate their surface area

from their diameter and

you won’t complain.

I met Frank

at my car and on the way

to the store Frank outlined his method.

I suggested a few things to make it easier,

we bought every round seed in the store and

Frank gradually refined his approach over the

next couple of weeks. He planned to use a ruler

to measure diameters, for example, so I

told him about calipers, then got him

permission to weigh them into

size classes at a research

station next door.

Frank’s final

experimental protocol,

like the hypothesis it tested, was

born with pain and frustration on

Frank’s part because of my

stubbornness. It was

beautiful!

One especially

difficult issue for Frank

was what to record; how to tell

whether seeds had germinated or not.

After much reading about seeds and germi-

nation, he realized that seeds swell as they absorb

water. By some point they’ve swollen so much that

the membrane covering them ruptures. Once that

happens, Frank reasoned, plants must either

grow or die and there’s no going back. He

couldn’t find direct support for that

idea, but I was thrilled with his

reasoning and agreed with

his definition of

germination.

Frank planned

to record when each seed

germinated, using splitting seed coats

to indicate when it happened. But I worried

that since Frank didn’t know how long it takes pea

seeds to germinate and he had many other things to

do including sleep, maybe there’s a way to estimate

germination time rather than measure it, so he would

not have to watch all day and night. Frank quickly

realized that if he held the seeds against the sides

of test tubes with tightly rolled paper towels,

he could observe at regular intervals

and record how many seed

coats had ruptured

by then.

That

way, Frank convinced me,

it wouldn’t affect the outcome

of his experiment if some seed coats

ruptured on the side away from the glass,

as long as that error was the same for all

treatments. He planned to observe tubes

each hour around the clock until the last

seed germinated. “The last seed?” I

worried. “What if some of your

seeds are dead?”

We compromised

on some arbitrary proportion and

he went ahead. In each of a set of test tubes

arranged randomly in test tube racks, Frank Spear

arranged 5 seeds from the same weight class in each

test tube, and he had enough seeds to replicate each

of ten weight classes several times over. He filled

tubes with water at Time Zero then carried

them around with him and checked every

hour of the day and night for

germinated seeds.

Just as his

formal argument predicted

would happen, small seeds germinated

first. Frank and I were ecstatic.

I made the

original observation and

asked a question that got him started,

but Frank Spear went through the complete

cycle of scientific discovery in his work. He began

with an observation from a complex real world

situation, pondered it in simple terms, thought

of a testable way to explain it, tested the idea

experimentally, analyzed the results,

returned to the observation and

interpreted it in light

of that analysis.

That’s what

professional research

scientists do for a living. Depending

on their discipline, it might take years

for them to complete even one cycle

but Frank Spear did it in one part of

one course in high school.

That’s incredible!

Along the way,

Frank learned a lot about

competition within and among

species, evolution of reproductive strate-

gies, plant anatomy and physiology, weather

and climate, community ecology, genetics, and

other things, including a great deal about what

Frank Spear himself could accomplish in his life.

I taught Frank little of what he learned about

any of those things. What I taught him, if I

taught him anything, was how to think

like a scientist, communicate with

scientists, and tell the truth

about what he did and

didn’t know.

Unless students

have at least some experience

of going through this cycle, on their own

or in collaboration with peers, they might learn

a lot of information and remember it for a while,

but without their own personal experience

of learning like that they won’t learn

much about science as a way

of learning things.

What a pity for anyone to miss out

on that. I’m glad I didn’t.

It was no mere

coincidence that Frank Spear

and the Pea Seeds unfolded as it did.

A little over a year earlier, after an experience

I had in the same room during my interview for

the job, I promised myself to let students learn

for themselves as much as possible instead of

teaching them. I wrote about that experi-

ence in Secrets of Silence in the

Classroom and told about it in

Stories about Stories.

You can find many

manifestations of this principle in

my stories in all categories.

Edited May 2022.