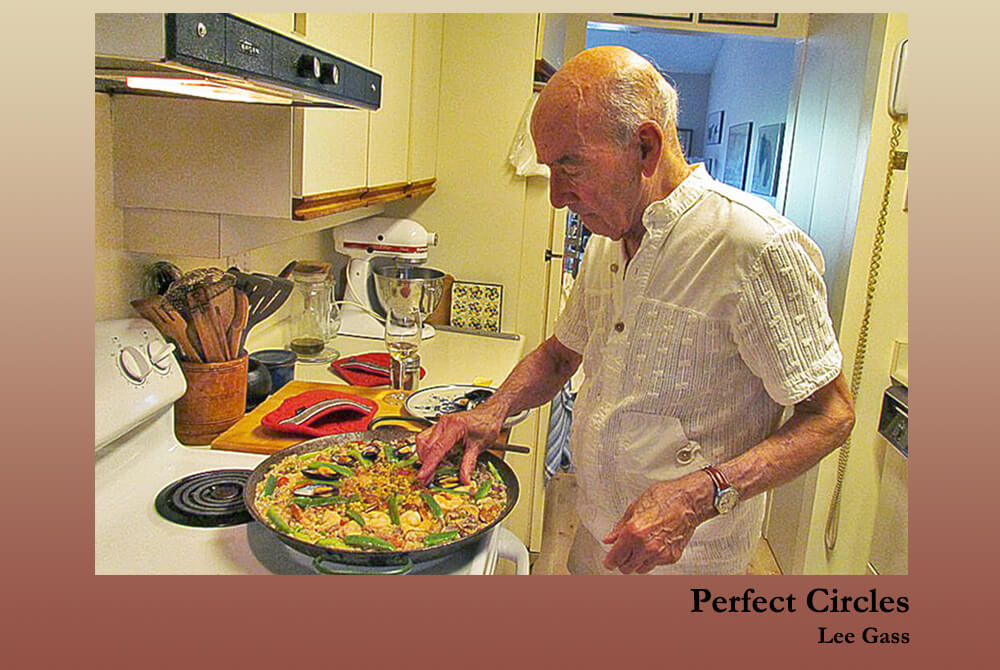

Luis Sobrino in his kitchen at home

making perfect

paella.

One great pleasure

of working in UBC’s Science One

and Integrated Sciences Programs is to

observe and interact with colleagues from

other science disciplines in the classroom. For

the one who is ‘up’ in front, colleagues’ engage-

ment brings surprise, uncertainty, enrichment,

and very often challenge. And engaging in

others’ teaching sows seeds for growth

in our own. That is one of many

rewards of real time team

teaching.

Here is an example.

Luis Sobrino

was the first physicist to

teach in in Science One, where he

taught two years before retiring in 1995.

Many things about his teaching were superb.

He was wonderful to work with and fascinating

to observe, and his articulate English prose, delivered

in the accent of his birthplace in Cadiz, Spain, inspired

me to use my own language more mindfully. His

stories about his hero, Galileo, captivated

me. They encouraged me to use more

stories from the history of

my own discipline.

His nearly

perfect perspective drawings

on the blackboard amazed me, especially

since so many teachers’ drawings done in the

heat of the moment, or carefully, are horrid. Luis

appeared to sketch them casually with no thought

or planning, but no student ever misunderstood any-

thing in any of his drawings. If you don’t already

know it, physicists and mathematicians draw a

lot of circles. Most must merely call their

drawings circles just as biologists

must label their drawings fish or

rats so we know what to

see in them.

Luis’ circles

were perfect. They had no

corners, flat places, innies, outties,

or any other irregularities (their radii

were constant), and it was impossible to see

where their ends met. They were perfect and

everybody knew it, including Luis, but didn’t

talk about it. Over the months I marveled

at his circles. As a biologist, I wondered

how he made them and how he came

to make them so well. Slowly, I

realized something significant

about his circle drawing

behaviour. It appeared

stereotypic to me.

Same starting place,

same speed, same direction, same

fairly large size that engaged his entire torso

in the drawing and allowed everyone in the room

to view both the result, the circle, and Luis Sobrino’s

perfect circle-drawing performance. That told me

when Luis drew circles, he engaged the same

muscles in the same way and the same

sequence every time , and it

gave me an idea of

something to do

in class.

One day

at the start of the class,

before anyone said anything serious,

I asked the class to tell me the difference

between ballistic and guided missiles. After a

few minutes’ discussion among themselves, they

realized that ballistic missiles are Newtonian

particles in motion. Once moving, their mass,

speed, and direction of motion determine

where they will land. Guided missiles

tune direction during flight, usually

using information about where

they are in relation to the

target to guide the action.

We talked for

a while about what would

have to be known to aim ballistic missiles

accurately or tune trajectories of guided missiles

and how missiles could get it, and when I was

sure they ‘got’ ballistic vs guided,

I gave a quick lecture about

the organization

of behaviour.

In 1974,

Ernst Mayr argued that

animals likely don’t control complex

actions by controlling each component

act independently. That would require vast

processing power, make coordination difficult,

and be too slow to work in the real world. Instead,

he thought, they package actions into complete

sequences he called behaviour programs, and

control them as coordinated wholes. Behaviour

programs vary in openness to modification

during execution, and he suggested

two kinds of factors influence

that plasticity.

First, he expected

short-lived animals with little

opportunity to learn from experience,

to have relatively closed behaviour programs

that may even be specified genetically. Similarly,

communicative behaviours like courtship, which

must be interpreted and responded to correctly

by other individuals of the same species, are

relatively stereotyped and closed

to real-time modification.

In contrast,

because foraging for food

and avoiding predators must be

performed under widely varying conditions,

it must be open to modification, especially

in long-lived animals who learn from experience

to execute the same basic programs many

ways. If predator and prey animals

had words for things like this,

“Chase Sequence” would

be a good one.

We discussed

a few examples of open

and closed behaviour programs,

then I asked whether anyone had noticed

anything interesting about Luis’ circle-drawing

behaviour. The class lit up and quickly agreed that

Luis drew the most perfect circles anyone had ever

seen. Luis beamed proudly. When I asked them

to predict whether that action was guided or

ballistic, all also agreed, including Luis,

it must be guided to be so good.

It was harder

to agree on a way to test

that hypothesis. Someone noted that

by Mayr’s definition, guided programs must

be open, and suggested probing them experiment-

ally with various perturbations. When a student asked

Luis to draw a perfect circle slowly and deliber-

ately, he failed and was surprised and

visibly embarrassed by that.

That

gave them the

sense they knew what

to do as scientists, so I turned

them loose in teams to devise and per-

form tests of their own circle-drawing. They

tried slow circles, fast circles, backwards circles,

upside down circles, and wrong-handed circles.

Overwhelmingly they concluded, again to

everyone’s great surprise, that Luis’

circle-drawing, and theirs,

was ballistic.

In a short

concluding discussion,

we wondered about the structure

of ballistic circle-drawing programs,

and wondered how they came to be ballistic

instead of guided. We tried to remember what

it had been like as kids to learn to draw circles.

Some described the head-drawing behaviour

of younger siblings, which seemed guided.

That led us to wonder whether programs

grow progressively more ballistic

with practice, and to wonder

how that happens with

no conscious control

or awareness.

The discussion

continued informally for

weeks outside of class, and I

gave interested students copies

of a paper I had published on a related

topic. Luis was not pleased that for the

next several weeks he was too self-

conscious to draw perfect circles.

Eventually he returned to his

normal perfect style

and forgave me.

In a talk

I gave at a national

convention of educators, Stories

about Stories, I told a favourite Luis Sobrino

story, about Galileo discovering the

concept of momentum in

a coffeehouse.

In a book

chapter I wrote about

surprise, Behavioural Foundations

of Adaptation, I discussed Mayr’s notion

of behaviour programs at length,

including their development

and control

In editing,

I realized that the

using the idea of behaviour

programs in Perfect Circles is a

perfect example of the value of theory.

No one has ever seen a behaviour program.

Mayr made up the idea to help understand

something. Others find it useful in the

same way. It is a figment of

Mayr’s imagination.

Edited January 2019