Interviewing me

for my first teaching job,

at a high school, Ernie Wutzke, the

Principal, took me to visit the room of

Art, the biology teacher I would replace

if I got the job. He said it was impossible

to predict what would happen in

Art’s classroom, and made it

clear he thought that a

very good thing.

When we entered

the room, three students were

at the blackboard arguing about details

of photosynthesis or DNA and the rest of

the class was fully engaged in the discussion.

Art was on his back, on a high workbench

along the window, a book for a pillow,

apparently asleep.

Ernie and I

stood at the back of the room

while the argument raged, with

no sign of life from Art.

After a while

the discussion took a turn,

as arguments tend to do, toward

the personal. “That’s stupid!”, a student

exclaimed, others responded in kind, and

it escalated. After letting it go for a while,

Art stretched, rolled slowly and silently,

but theatrically, onto his side on the bench,

propped up his sleepy head with his fore-

arm, and everyone in the room stopped

and looked at him, listening but

not yet hearing anything.

They knew what he was going to say!

After what

seemed like forever,

Art commented that while

at the beginning of the discussion

everyone had been listening carefully to

everyone else and learning from it, he didn’t

think anyone was listening anymore. “You might

learn more if you listened to each other instead of

trying to prove how much you know”, and he

rolled back into his napping position,

went back to sleep, and the

discussion continued.

Ernie winked

at me and we left

the room.

He said Art

was the best teacher he’d

ever known, but in all the time he’d

worked there, Ernie had never once

actually caught him teaching.

More than any of the

other teachers he’d known, Art

tried new things, some of which

flopped badly and he

learned from

that.

“But if

you’re a tenth as

good as he is“, Ernie said,

nailing me in the eye

with his own,

“you’ll be

great.“

I never

actually met Art, but

for the last 56 years he’s been a

hero of mine and an influential mentor.

During those few minutes in Art’s class-

room, I learned one of the most valuable

lessons of my entire teaching career:

The less I teach them, the

more they learn.

Teaching in the

same room the next fall, I

saw how difficult it was to keep

my mouth shut and allow students

to explore ideas on their own

without my needing to

profess to them.

Eventually I

realized that it was easier to keep

my mouth shut when my hands were busy,

so I carved small sculptures in chalk in class

with my pocket knife. At the end of class as

I congratulated them on a job well done,

I presented tiny sculptures to students

who had contributed significantly

that day, and taxpayers footed

the bill for the artwork.

After a month or

so of my doing this, carving

had become much more than a cheap trick

to help me keep my mouth shut. It was a symbol,

a signal, a trigger, a ritual, and an important

component of our classroom culture that

grew more effective the more

we practiced it

together.

The more

students practiced talking

with each other and the more I

practiced staying out of their way,

the more they learned, the more

I learned, and the more

we all enjoyed the

process.

As if by magic,

the simple act of taking out

my knife, beginning to carve, and

keeping my mouth shut impelled

students to discuss things

deeply with each

other.

Teachers are like

Pavlov’s dog salivating when Pavlov

rang the bell. When students elicit teaching

behaviour in us, we teach. Teaching’s not

all we can do, though. We can also

elicit learning behaviour

right back at them.

Fortunately,

students are like Pavlov’s

dog about learning from and

with each other, so it

happens easily

if we let

it.

We

now know that

interactive engagement among

students is the #1 most significant factor

in development of conceptual understanding and

problem-solving ability, at least by under-

graduate science students.

Given the

universal compulsion of professors

at all levels to profess, it follows that we must

learn to remain silent in our classrooms. In

the various ways it emerged in my career,

the cheap trick of carving chalk

in class served me well

for decades.

(Can teachers even carry knives anymore?)

Later, at the

university level, I peeled the skins

of fruits and vegetables slowly and contemplatively

with my pocket knife as students filed into class. Listening

carefully to relaxed conversation as students came

in and speaking mainly in response to direct invi-

tation, I slowly nibbled on peels until it

was time to get to work.

That was

a first-year university

biology course for racial minority

students in 1969. Triggered often by my choice

of fare for the day, sessions began with a short

discussion of the skins of things. You can

imagine the variety of examples

available. It’s huge.

Given the

racial tensions of the time,

some of those discussions were

hilarious, depending on little more

than what I happened to be peeling

that day and whatever students had

to say about it. It loosened us up

for the work we were there

to do together.

Back

in high school teaching,

I sketched students in notebooks

and gave them what I’d drawn. I exam-

ined snakes in snake cages along the window,

gazed out the window, watched 60 sealed gallon

jar aquatic ecosystems on shelves in the window

struggling to survive. I studied architecture

I’d studied dozens of times before

and watched clouds move

up in the sky.

I don’t know

about you, but for me

it’s hard work sometimes to

not teach, or preach, or

whatever you want

to call it.

Art

pretended to take

a nap. Maybe he did nap; I don’t

know. Maybe he set some special sort of

alarm to alert him when his students

needed him to intervene.

As a

university

professor later, I took

small stone sculptures with me

to classes, committee meetings, office

hours,

and PhD exams, and sanded them

quietly and unobtrusively while

participating fully in dis-

cussions. This went

on for years.

People came

surprisingly quickly to expect

it from me, and no one complained.

Then, again rather easily, they

ignored it and attended to

the business at

hand.

Here are two

of those early sculptures,

Beast, in jade, and Flight from the

Island, in rhodonite. Each is between 1 1/2

and 2 inches high, not counting their bases.

They are tiny, and I sanded both of them

in meetings and classes.

Beast was

a graduation gift for a

student in my first-year biology class

who had worked in my hummingbird lab until

she graduated. We published her honours thesis

work. Zena Tooze later studied wolves for her

MSc, then founded and directed a primate

rehabilitation centre in Nigeria,

Cercopan.

Beast.

Jade, cocobolo.

Photo by Lee Gass.

Flight from the Island.

Rhodonite, slate.

Photo by Stuart Dee.

By a similar

token, meetings with obsessive

note-takers were much more effective

when we conducted them outside, walking

briskly through whatever the weather was at

the time. Note-takers rarely listen as well as

they could anyway, so walking while

talking helped them listen.

Many people

in universities, faculty and

students, are infected with the DISEASE

of note-taking, in fact. That turned my

office hours into opportunities

to exercise.

Walking while

talking and talking while

walking kept us breathing, kept

us thinking and feeling and

cleared the air for us

to listen.

We need to keep

breathing to keep walking.

That keeps us saving up air, keeps us

listening, and we don’t say anything until

we have something worth saying. It

makes it possible, really, for

us to converse with

each other.

When Maria Klawe

became Vice President at UBC,

we discovered she did something similar

to my sanding and chalk-carving “thing” in

meetings and classes. Maria painted water-

colours in meetings, even Board of Directors’

meetings and meetings with ‘suits’ downtown.

Now, as President of Harvey Mudd College,

renowned mathematician and computer

scientist, she still does. In two wonder-

ful videos, Maria discusses that

practice and gives

examples.

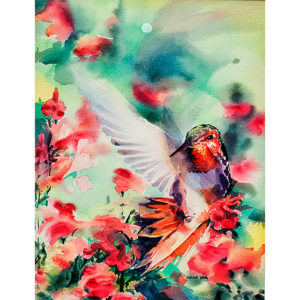

Maria gave me

a painting of a male rufous

hummingbird for my 60th birthday

and it hangs in our home today.

I hope she painted it in a

Board meeting.

Male rufous hummingbird and flowers.

Watercolour painting

by Maria Klawe.

Keeping your

mouth shut while you teach

is not rocket science, people!

And it’s a no-brainer

once you think

about it.

Get over it.

It’s not our job to teach

our students. Our job is for

our students to learn, which is a

different breed of cat than

teaching them.

Once the

magic starts, all we have

to do is shut up, stand back, step

out of the way, and let it happen. We

usually have to stir up some kind of trouble

to get things going and intervene some-

times to guide it, like Art did with

his teenagers.

But we

don’t, can’t, and

should not even try to

“make” it happen. The magic

happens by itself.

As far as I’ve

been able to tell, that’s

how creativity works. I’ve said

what I mean by creativity in

other stories. I’ve also said

students must do that

part for themselves.

It’s often easier

for them to do it in groups,

but they have to do it

themselves.

Not just students,

either. Everyone. Overwhelmingly,

my experience has been that students are more

than happy to learn creatively, as long as

their social environments encourage

rather than discourage

that.

It sure beats memorizing stuff!

It

beats reading

what memorizers memorize,

too! Can you imagine reading that

all your life? What a drag and a lot

of work for so little gain! it’s a

perfect lose-lose situation

for everyone!

Not only

did I not want to waste my

own time doing that. I didn’t want my

students to waste theirs memorizing. What

an insight it was for me to realize that I

didn’t need to test what they knew

to know what they knew.

If I tested for

understanding and expected

them to use knowledge to demonstrate

it, I’d get both. If they don’t understand what

they know they can’t use it, regardless of

what they know, so I had to

teach for under-

standing.

But

I had to shut up

every once in a while

and let it happen!

I often

tell the story about Art

in talks. Though I think I called Art

Al in one of them, here are two examples.

Stories about Stories and Making Magic Together.

An earlier version

of this story is in the book

Silences in Teaching and Learning

Here is a review of a reading

from that book.

When Gary Poole came

to UBC to direct our Teaching

and Learning Centre, he and I talked a

lot about our dreams for the future and how

to collaborate to make them real. We usually

did this practically at a dead run. Across

campus, down the road to English Bay,

along the beach trail and part way

back, up the cliff on a steep

trail, and back to our

offices for the rest

of the day.

If either of us

had something hot and

burning to say on the way up

the cliff but couldn’t say it for lack of

air, we stopped as briefly as possible

to get us going again, still out of

breath but able to speak

and listen.

In telling

others about those meetings,

Gary referred to my style of communicating,

punningly, as “running meetings”. I think he was

daring them to meet with me, and many of them

took him up on it. It was great exercise while

it lasted. Now I get exercise

in other ways.

Conducting Running Meetings

A brief, two-stanza operating manual.

Conducting

running meetings is both an

art and a subtle skill. So much depends

on conditioning that breathing rate, which

you easily hear, is a reliable indicator of

how any given meeting is going at

any given moment on any

given walk.

As walking

speed increases, so do meta-

bolism and rate and depth of breathing.

Talking competes with walking for oxygen,

so you can gently push breathing rate high

enough to favour listening over speaking,

then slow or even stop so your comm-

unicants can speak and you

can listen.

Often when

Gary Poole and I

charged up the hill, our

talks reached a crescendo near

the top of a steep, punishing trail up

to the plateau, just when we were most

out of breath, most in oxygen debt,

and most aware of the pain

of Lactate Burn.

Ideas churned

faster than either of us could

have articulated but neither of us could

talk about anything. But we remembered,

talked when we could talk, and applied

some significant fraction of those

ideas in our work.

The Institute

for the Scholarship of Teaching

and Learning grew out of a walk

and a talk like that.

Gary Poole

and I having brainstorms

near the top of a steep climb when

we were out of oxygen reminds me of

Luis Sobrino’s response when I asked

him in Science One class one day

where he, a theoretical physicist,

got his best ideas.

Instantaneously,

Luis said ‘On the bicycle.’

When I grilled him

further about it, he told us about

his daily ride from home on a boat in False

Creek, through Jericho Beach and Spanish Banks

parks to the bottom of the hill up to UBC. It’s the same

hill as before, but more gently on a road and sidewalk

instead of a steep trail and biking instead of huffing

up a trail, less than a kilometer from where

had our own epiphanies.

Every morning,

rain, shine, snow or ice, Luis

stashed his bike in the bushes, stripped

off all his clothes, and swam in the ocean

before riding up the hill to his office in the

physics building. His best ideas came

a little lower on the hill than ours,

near a tree where an eagle

perched sometimes

on my own rides

up the road.

For what

happened to my

consciousness near the bottom

of a steep descent, see Lactate Burn.

Edited May 2022