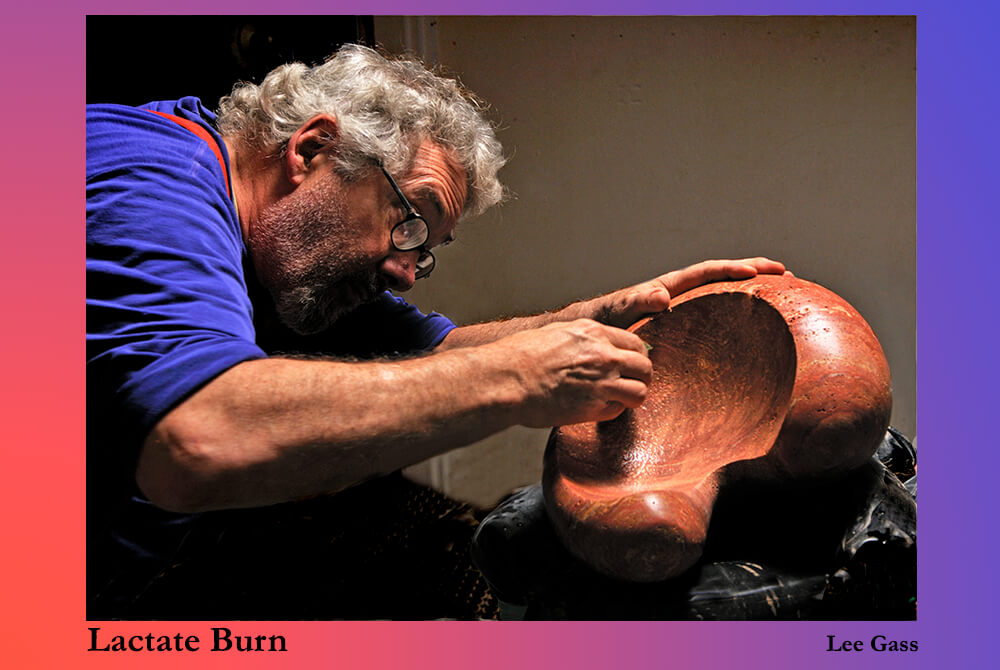

Forearms feel lactate burn sanding Red Recursion.

Photo by David Shackleton.

Lactate Burn

We got our

TV at Christmas when

I was almost 10 years old

and there was just one

channel.

I don’t

remember any of it

before the 1952 winter Olympics.

Except for boxing matches and baseball

games on the radio, that was my

introduction to world-class

athletics.

I became

totally absorbed in

what Olympians did. It surprised

and embarrassed me to discover that superb

performances in individual events like skiing could

bring me to tears. That realization influenced many aspects

of my life, including that biographies, even fictional

ones that only might have been real, became

favourite reading material and

I read any of it that

I could find.

When Stein Eriksen

won the giant slalom in perfect

1950s style, he instantly became my hero

and athletic role model. I felt profound emotional

and intellectual responses that stayed with me for years.

The feeling of what happened then is still with me now,

informing how I look at things, respond to

situations, and think about them.

Gradually, feeling

those feelings and thinking those

thoughts, over and over in different events,

I realized something important. My strong

responses were not limited to athletics.

High-level individual performance

in anything fascinated me.

I wanted to understand

that and still

do.

Nordic ski

jumpers still dominated

that event with their classic, arms

forward form, and some teams tried the new,

aerodynamically superior arms back

form that still prevails, but

with little success.

The real ski

jumping hero at Oslo, to my

mind, started wrong and ended worse.

He jumped after his skis passed the lip, pushed

down only on air, landed bad too high on the hill,

tumbled and cartwheeled to a stop, then

bowed repeatedly to crowds and

cameras, and strutted off

proudly.

I laughed so hard that

I cried again!

I was good

enough to train with the

ski team in college, but not nearly

good enough to compete in any event.

I was an awful ski jumper and had

neither strength nor endurance

to compete in cross country.

Downhill

was my favourite alpine

event, but I never once completed

a downhill course with a clock

on me without falling.

I made it through

the hairiest, scariest, most

dangerous parts of downhill courses,

where I was most likely to have broken

my neck, then fell before the finish

line where it was safe and

slow and easy.

Here’s

how I found out

why I fell. It has every-

thing to do with

lactate burn.

Why they

kept me on the team had

nothing to do with my skiing. But that

was before portable video cameras

and I was a good substitute.

I was better than

a camera in some important ways,

actually. I could watch you come down

a slalom course, then tell your run

back to you in a story.

“Overall,” I’d say,

“you started strong and

entered the first gate just right,

but came out of it low and lost

time before the second and

more more getting

through it…..”

“Now, back up

to your approach to the

first gate. You tell me what hap-

pened in the next few seconds, I’ll

tell you what I saw, and then you

tell me whether you remem-

ber doing it that way.”

I was a

human video camera

with running commentary and

analysis and instant, slow-motion,

playback. It was amazing, and it

kept me on the team for

a while.

Years later,

former teammate Peder

Anderson asked me to watch him

come down a slalom and I did. At the

bottom, I told him back his run as we’d

done before and discussed how his time

might be improved. Then I asked him

about something in his skiing that

I hadn’t noticed before.

“Why

did you make

that loud Pahhhhh! sound

when you turned,

Peder?”

“Oh that,” he

said, “that’s so I’ll

remember to

breathe.”

Remember to breathe!

Suddenly I

understood why I had

fallen near the ends of downhill

courses when I was being

timed!

The hairiest, scariest

most dangerous sections of courses,

those my teammates referred to as ‘interesting’

and spoke of with pride and enthusiasm,

scared the daylights out of me.

I got so scared

I held my breath!

By the time

I got to the bottom of

the hill I was out of breath,

out of oxygen, my lactate-burned

legs wouldn’t support me,

anymore, and I fell.

Lactate burn to

the max!

You know the

feeling. Legs sting like

fire on long flights of stairs.

Too many situps too fast,

hill too steep, run

too fast.

What Nancy Martin

wanted to know

about that.

When

Nancy Martin was a

student in a course called

The Sizes of Things, she had

a brilliant idea about lactate

burn. She was a long

distance runner.

She’d wondered

for years about something

about running.

On average, long

races are slower than short

ones. Why? That’s obvious and every-

one knows it, but she wanted to understand

it on deeper levels. How much slower do

they run in how much longer races?

What makes it happen

that way?

She thought world

record running speeds at all

distances would follow one simple

function called a power law, but she

found six. Six power laws, each clean

and clear, for short, middle, and

long distance races, differing

for male and female

runners.

Three things stand out

about that result.

First,

Nancy’s data were

exceptionally well described

by the power laws, statistically. Her

plots were clean, tight, and straight

on log-log graphs, just as she’d

predicted, but there

were six of them.

Scientists

call it beautiful when

it comes out like that, not

just because of pretty graphs

but because strong results

need strong explanations.

A

second aspect

of Nancy’s discovery is

harder to describe, and I

can only sketch it for

you here.

She expected

power laws because she

thought running speed would be

governed by physiological processes

she thought would be governed by power

laws. Her arguments and predictions

made sense and she did find power

laws. But why she find

so many of them?

Different power

laws for men and women

was not surprising. But three sets

of laws over three ranges of distances

implied different processes governing

running speed for the three

ranges of distance.

That was

interesting and exciting

news.

It was also

perplexing news for

Nancy because her strong result

begged a strong explanation

and she had to imagine

what it might be.

Nancy did identify 3

separate mechanisms, each

governed by power laws and each

related to lactic acid production

and lactate burn.

It would be

far beyond our scope

here to explore her explan-

ation in detail. There’s a longer

version of the story in Architects

of Their Own Education.

The third

aspect of Nancy’s work

is that as far as we were able to tell,

no scientist had ever asked her question

in a way that could be answered by

what she found and how she

explained it.

It is beside

the point of this story

for me to tell you that, but

it’s something worth

celebrating.

The main point

here is that lactate burn

comes with the territory when we

push physical limits, whether climbing

long flights of stairs, expending extreme

effort for several minutes in downhill

races, or sustaining three weeks of

effort in the Tour de France

bicycle race all up and

down the place.

Or carving rocks.

Carving rocks is

both supremely enjoyable and

a lot of work. Every step of the way,

from ropughing out with hammer and

chisel, pneumatic hammer, or grinder

to final sanding and polishing,

is work.

When physicists

say “work”, what they are

talking about is simple: spending

energy to apply forces that make

things happen in the world,

and that’s what I’m

talking about

here.

Sculptors

who need to finish one

piece and get on to the next one

know lactate burn. They also know

how important it is to

manage it.

Here I am

on the last day of sanding

Red Recursion, after weeks of

all-day-every-day sanding

with coarser abrasives.

Earlier stages are

always about form, not surface,

about resolving forms, integrating

them, bringing them to rest perceptually.

Smoothing rough curvature – – taking

away high parts until low

parts are gone.

Later, carving

is more about the texture

of surfaces than their form. At the

finest scale, finer and finer scratches

smooth the surfaces of stones

and polish them.

The harder you

press the abrasive into

a stone and the faster you

slide it along, the deeper the

scratches it make and the

more stone you move

in a day.

If, which is

what Nancy Martin

wondered about running,

you can keep doing it

that long.

Generating the

forces to do all that takes

energy and oxygen, and it generates

lactic acid if you work hard enough. If it

builds up enough in your muscles, its

burn will be enough to stop you,

literally, in your tracks.

In that situation,

the only choices are to

breathe deeper and faster, if

you can, and/or work slower. That

is a law of nature and there’s

no getting out of it.

But maybe

there’s a way of getting

around it, I wondered.

Everyone

knows there’s a limit.

At some point you work

slower automatically, whether

you want to or not, and lactate

burn makes you do it.

But

when more muscles

do the same amount of work,

especially when work floats among

them as it happens, muscles don’t run out

of oxgen, little lactic acid gets formed,

more energy is available for the

work, and we can keep up

the pace.

That’s simple

and obvious, and every

little kid with a bike knows

it well. It was a real “Aha!”

experience to rediscover

it in sculpting.

Without really “seeing”

what I’d been doing all my life, I’d been

managing lactate burn. All that time, the

burn been telling me to stop doing one

thing for a while and do some-

thing else. That was the

law and I obeyed

it.

In the image,

I am bent over my hand, arm,

shoulder and back are engaged in a

coordinated set of motions that

slide the abrasive over exactly

the curvature I was sanding.

I might have

sanded standing up with my arm

straight, and used only only my wrist and my

shoulder to produce the action. That would

have been a killer. So would

samding sitting down.

The burn

would be concentrated

in a few small muscles in my forearm,

build up quickly, and scream at me. If I pushed

too far into the pain, I could ruin the sculpture

and my arm. Lactate burn keeps me

from doing things like that.

Instead, I

sanded in ways that

gave more control, engaged

arms, shoulders, back, legs,

and neck in the motions,

and afforded a much

better view.

Spreading effort

around like that kept the burn

tolerable in any one muscle, let me work

harder, faster, longer, and sand more stone.

I spent less energy to do more work, and

suffered less stress on my body

over the workday.

My bench

goes up and down.

I shift workpieces on sandbags,

blocks and wedges. I carve left-

handed for a while. I stand on a

pallet. Whatever.

The more I change

how I do it, the more I move

lactic acid around and the more

I accomplish in a day.

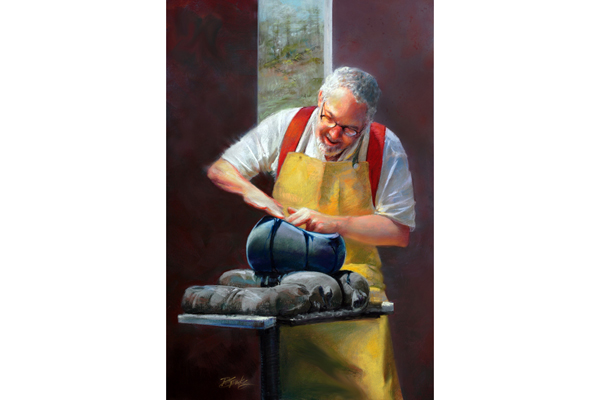

In this pastel painting by Perrin Sparks

I am spreading the effort around

in sanding Heart of Anima.

Remembering the

1952 Winter Olympics while

editing reminded me how strongly

that and similar vicarious experiences

reinforced my love of biographies

and biographical novels, mainly

sports and adventure heroes.

And that, in turn,

reminded me of something

about my Mother.

For several years,

after she was librarian at a

community college 18 miles from home,

Mom was librarian at the elementary school

in the same community, Weed, which was

crazy sports-mad in those days.

Mom knew boys would

read anything, as long as it was about

sports, so she bought every sports book she could

find and boys checked them out like crazy. She

got them hooked on books, and got girls

hooked on whatever girls liked

to read at the time.

For the boys, there were

at least Joe Louis, Babe Ruth, Lou

Gehrig, Mohammed Ali, Joe DiMaggio,

Jackie Robinson, Yogi Berra, Rocky Marciano,

Jack Johnson, Jack Dempsey, Jesse Owens, and

maybe Stein Eriksen by then. If it was

about sports, boys read it, talked

about it, and came back

for more.

The teachers didn’t

like that. They thought kids

should read “real literature”, not

just sports, and be serious about it. For

Mom it wasn’t about real literature, whatever

that means. It was about getting kids hooked on

books, no matter what they were about. As long

as they loved it, she didn’t care what they

read. She also knew those kids were

serious about their reading. It

was all they could talk

about.

She didn’t care what

I read when I was little, either,

though she did sometimes caution me

about whether I was ‘ready’

to read something. I usually

took that as a challeng

and usually she

was right.

Stone sculpting

as an athletic event

A few years ago

I did something stupid with a

big tool for too many days in a row,

and damaged my back and it cost

me a few months away from

sculpting.

I’ll tell the

full story later, but it’s

worth mentioning here that a key

aspect of my complete recovery was

a visit to the UBC Sports Medicine Clinic.

My GP said she wanted to send me to the clinic,

but would have to justify it by arguing that

sculpting is an athletic event, and wanted my

opinion. When I got to the clinic, Dr. Jack

Taunton laughed and said “Well of course

sculpting is an athletic event!”

He cured me

forever with a simple

exercise.

First published in the Vancouver Observer

Edited July 2021