This assignment

is completely optional. It is

the most powerfully effective way I

have discovered to empower intellectual

growth but would be worthless if taken lightly.

It is an interactive dialogue between us that

invites you to examine, communicate, and

transform how you operate at success-

ively deeper and more signifi-

cant levels.

Submit

responses to the following

5 questions under a title page that

includes at least your name and the date.

Each time you submit the assignment attach all

previous submissions with the most recent on top.

Begin each response on a separate page. Clearly

indicate which questions responses address.

Type single-spaced with wide margins,

single sided. Use all of your

writing skills.

The depth and

quality of writing are much more

important than quantity, but it would be

difficult to express anything of value in less

than a solid paragraph. Your responses

can be as long as they need to be

and you can submit them as

often as you want.

Use this exercise as

a way to deepen your appreciation

of yourself as a learner, to express that in

writing, and to get feedback from us about it.

We will read and comment on what you write, so

leave plenty of room for comments (wide margins

and single side). If our comments trigger responses

that can’t wait, that’s great. Don’t wait. Do it

again while the impulse is hot. Put every-

thing you have into this assignment. It

can dramatically and permanently

transform what education is

for you, forever.

Questions

One

What are the best

things about this course so far,

in terms of your intellectual development

and growth of your awareness of human

ecology? What are the most important

ways in which this course has

facilitated your growth

in these areas?

Two

What are the worst

things about this course so far in

terms of your intellectual development

and growth of your awareness of human

ecology? What are the most important

ways in which this course has failed

to facilitate your growth

in these areas?

Three

What have been your

most important contributions

so far in this course to your intellectual

development and growth of your

awareness of human ecology?

Four

Discuss the most

important factors that currently

block your intellectual development and

growth of your awareness of human ecology.

What keeps you from achieving even more

than you already have in them?

Five

What mark do you

intend to receive in this course?

What is your responsibility to see

that you receive this mark?

What is ours?

I developed

this assignment in 1969

when I was a PhD student in ecology

at Oregon. Carlos Galindo and I perfected it

in a course for non-scientists on Human Ecology

at UBC. I’ve used it in several kinds of courses since,

successfully for those who tried it, sometimes dramatically.

The depth and power of students’ responses astounded me

and the development they exhibited through the experi-

ence impressed me. Those things underline the idea

that the deepest, most important learning is

metacognitive and reflective, and is

personally transformative.

One student produced

about 160 pages of typing in all,

with voluminous written comments by

Galindo and me each time. This was only a

small part of the work she did in the course,

but she claimed that it was the core. Carlos

and I both learned to write, almost

literally, from that student.

As I hinted above, engaging

in this exercise is a powerful stimulus for

intellectual growth, or the ability to know and

understand things. That is one of its benefits and

that benefit is transferable to many other situations,

in many other places and times. Getting better at

knowing and understanding one kind of thing

helps later to learn other kinds of things,

especially if they are similar

in some way.

Another benefit

flows from the fact that the

exercise is about what all courses are

about: learning the ‘stuff’ of some discipline,

learning to learn it, and hopefully learning to

love at least some part of it. In this case and all

others, ‘stuff’ includes not only what we know,

but how we know it, how we come to know

it, think about it and speak about it, how

we know we know it, what we will or

won’t believe about it and so on,

almost ad infinitum.

‘Stuff’ does include

all that. But even if all the assign-

ment did was ‘force’ students to express them-

selves as active learners, it would help them learn

the material. Much more important than any of that

is that it helps them see that they, themselves, are

responsible for what, how, how much, and how

well they learn, how long they remember it,

and what they learn about how they

learn while they’re learning it.

The first UBC

students were science

outsiders whose academic homes

were in Arts, Humanities, or Elsewhere.

they had put off their science until the last

possible instant and couldn’t graduate without

taking some science and ended up in my course.

Some students knew they knew everything worth

knowing about Human Ecology coming in and

some thought they knew nothing. Both were

wrong. Virtually none of them had even a

clue about science as a way of

learning things.

Without saying

so directly, the exercise helped

those who “knew” that they knew nothing,

or habitually suspected so, to see that they were

wrong about that – – that they could learn scientific

material and think, speak, and write scientifically.

Those who thought they knew everything,

usually young males, learned

similar lessons from

the work.

It helped all

students realize that capabil-

ities they developed in their own disciplines

were helping them in science, and that develop-

ing transferable skills in science would help them

everywhere else. It helped them integrate

their knowledge and their

understanding.

Through years

of engaging in this process

with students, Galindo, I, and others later,

noticed some interesting patterns.

For a surprising

number of students, the best and

worst aspects were the same. It was more

surprising that few of them realized until later that they

had been bragging and complaining about the

same things! It was hilarious, actually,

especially since both arguments

were so strong.

It was

fascinating to see how

individuals’ responses evolved over

time, particularly in relation to what was

happening with the second pair of questions at

the same time, about personal contributions and

blockages to growth. Here are my two favourite

examples of that pattern. This pair of com-

plaints also appeared often in student

evaluations of my other courses.

******************

“I’ve never worked so hard in my life.”

vs

“You never tell us what to do.”

******************

and

******************

“You never tell us what to learn.”

vs

“I’ve never learned so much in my life.”

******************

Some students

seemed not to understand

at first what it means to “intend”

to receive a certain mark in a course, or to

intend to do anything, really. They wrote as

if they thought their own volition as active

learners had no bearing on what they

learned. But, not yet seeing them-

selves that way, how could they

think otherwise?

Good grades take

hard work. That’s a no-brainer

and everybody knows it. But hard work

and smart work are not the same. The exercise

helped them discover the difference, particularly in

response to comments we made on their writing.

In an important sense, it made them smarter

and helped them direct their learning

more effectively.

Some students

conflated intentions with hopes,

as the following pair of responses to Questions

3 and 4 illustrates. Again, individuals often didn’t

seem aware at first of a causal connection between

their own behaviour and the consequences of that

behaviour. Some were annoyed that we would

ask them to comment on how we would judge

them, as if that were all our affair

and none of their own.

******************

“I’m hoping for a high grade.”

vs

“I’m not doing anything

to make it happen.”

******************

When students

expressed pairs of statements

like these as complete sentences, after

they realized they’d paired them, they usually

used ‘but’ to conjoin them. That in itself

was revealing and opened

insights.

******************

“I’m not but I hope.”

“I never but you never.”

“You never but I’ve never.”

******************

Usually in that kind of case, it would be more

accurate, more open, and more direct to say

******************

“I’m not and I never,

whether or not you ever,

AND

I’m hoping for a miracle.”

******************

Noticing

patterns like that

helped us respond more deeply

and effectively and to coach students

in their effort to make good on what

emerged in the exercise as real

possibilities that they could

make come true.

One of

the more interesting

patterns that emerged was that

for some students, the best aspects of the

course and their biggest blockages to growth

were the same. That made no sense to us at

first glance, especially without the

specifics that fleshed it out.

But

consider a student who

already knows a lot about Human

Ecology coming in and is proud of (usually

his) ability to demonstrate that knowledge but

the course cramps his style. He’s used to demonstrat-

ing knowledge and understanding, not interacting with

others to create them or acknowledging, embracing, and

bragging about his own ignorance. That one issue could

easily be his greatest opportunity, challenge, sense of

accomplishment, AND blockage, all at the same

time. It was wonderful to watch it happen.

An important

outcome of these exchanges

was that although many students were

quite aware of significant contributions they had

made to their own growth and considered that aspect

of the course the best, they still felt blocked, and they were

blocked, by their own poor attitudes about their ability.

This, like most of the other cases, is a classic

example of cognitive dissonance.

******************

“I am performing

at this level but I am incapable

of performing at this level.”

******************

One of our most

important tasks in commenting on

these kinds of responses, and on others, was to

help students see pairs of statements like these

as dissonant: How could both be true?

When we used the Continuing

Assignment in any course, my assistant

and I both read and commented on all responses

by all students to all questions, sometimes at length, and

returned them promptly. We often commented on each other’s

comments as well. It helped handle the load that there was no

‘due date’, so we tended to receive submissions one or a few

at a time and could get them right back. Perhaps most

surprisingly of all, nearly all students in some courses

participated fully in this time-consuming

exercise that carried no credit

or brownie points.

Our intention was not

to teach students anything about

themselves in commenting, but to help

them discover it for themselves. In particular,

we tried to help them identify, acknowledge, and

resolve paradoxes like “How can my best and worst

things be the same?” Since most students didn’t see the

relationships among questions at first and we didn’t

tell them, we needed to help them to see, feel, and

take advantage of that depth to improve

their learning process and keep

tuning it forever.

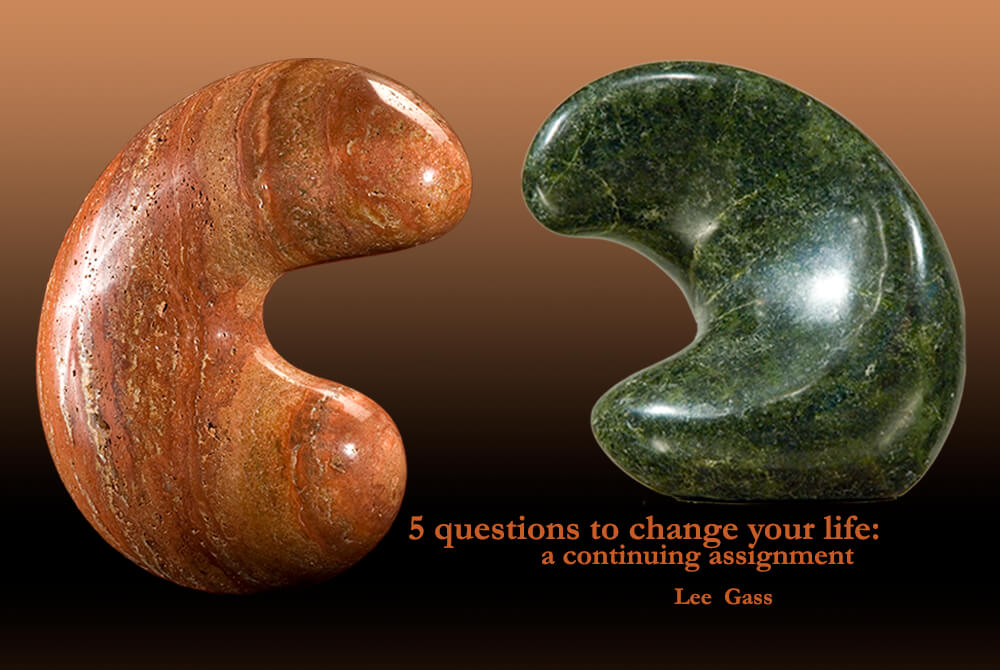

The image

accompanying this story

illustrates an important feature

of the assignment, which is both iterative

and recursive. It is repetitive in that students

responded to the same questions repeatedly, and

self-referential in that the process itself evolved with

repetition. The image features my Recursion sculptures

in serpentine and travertine. Carving them helped me

explore self-referential, iterative processes in learning.

Using those two sculptures to illustrate, I wrote

about those concepts at length in The Notion

of Creativity in relation to science,

art, and learning.

When I took an

Evelyn Wood Reading Dynamics

course in 1967, our performance increased

so fast that everyone in the course ran up against

“I am performing at this level but I am unable

to perform at this level,” which blocked our progress.

I started as such a slow reader that I was reading 4 to 6

times faster than I’d ever read when I hit that wall of dis-

belief in the third week, and everyone hit it at about

the same time. Of course the course was prepar-

ed for that and proved to us that we

were really doing the im-

possible.

With the same

very simple test, they scrambled

our notions of what reading is all about.

But that is another story. That $500 course

was one of the best investments I ever

made in my education.

Edited May 2022.