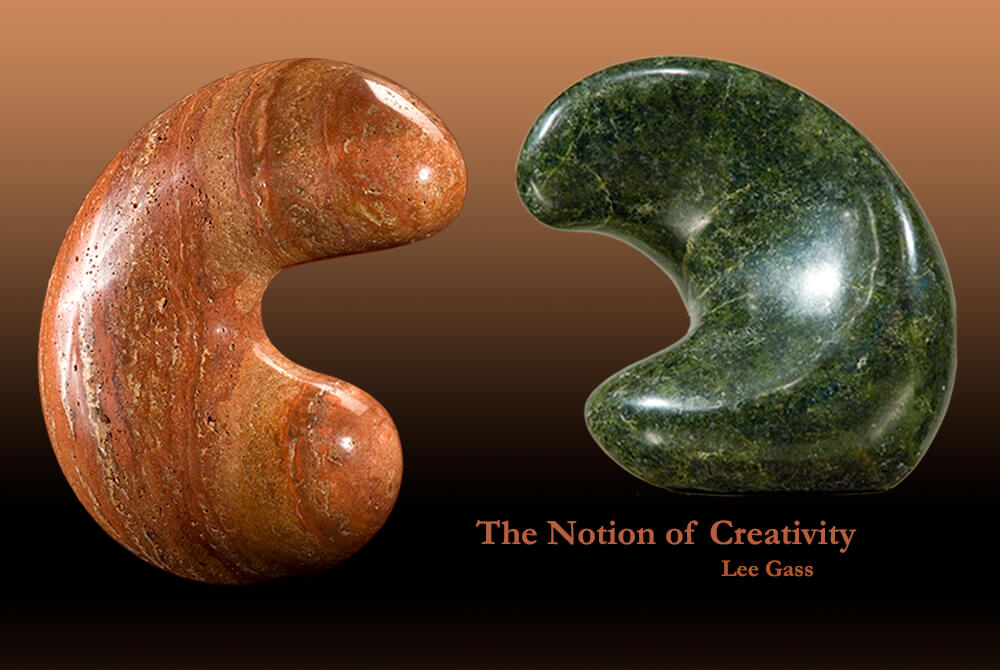

The Notion of Creativity

In my work

as a university professor,

questions about where ideas come

from were central to everything I did in

research and teaching. Now as a full-time

sculptor, they are the very essence of my

work. Creativity and innovation are

so important in our culture, and

in every other, and that

makes it good to

understand

them.

Here I will

describe the evolution

of a series of sculptures that began

on a camping trip with my kids on the

Yalakom River in autumn 1983. It rained

the whole time and everything was muddy,

but we kept a nice fire outside our

tent and had a great time.

Since I was soaked

to the bone anyway, it seemed a

good time to wade in the river and look

for rocks. The rich green colour and overall

shape of a hunk of serpentine appealed to me

and I brought it home. During quiet times

on the long drive back I thought about

the rock, held it on my lap,

and visualized its

form.

When we

see faces and elephants

in clouds and stones, psychologists

say we’re projecting experiences of

our own inner lives outward and

imagine seeing them there.

I live my life as a

projectionist.

The rock was still

just a rock on the way home

and for some time after, but it reminded

me of the circle-arrow ‘reload’ ikon in browsers.

Browsers had not yet been invented and only nerds

in universities used the internet. But I knew the

symbol. Maturana used it to indicate the

autopoietic, self-recreating nature

of all living systems.

The shape of a rock

led to a sculpture in serpentine,

Recursion, and pointed to the essence

of human and animal intelligence

and learning. What

a rock!

“Recursion” refers

to recurring, self-referential

processes that modify themselves

each time they occur. Successive cycles

build on each other, ‘recursively’. Smooth,

automatic body temperature regulation

is a simple example of a recursive

process that maintains sta-

bility by changing

itself.

Some systems

are anything but stable.

Anything that happens reinforces

everything else and once it begins, unless

something from the outside gets in the way,

they accelerate to inevitable conclusions

very much different than their

starting points.

In

Falling in Love and

Falling in Hate, everything

reinforces everything else,

things accelerate, get

out of hand, and

climax.

The thrill

of discovery is

similarly explosive.

In research, teaching and

learning, sculpting, ice cream

making, anything else we do.

Most likely, there’s still

something there to

discover.

Within a

few weeks, I had

completed the small green

serpentine Recursion. For the

next 25 years, the whole idea of

recursion grew ever more

central to my work

and to my life.

I fell in love,

felt daily growth in our

relationship, and gave the

sculpture to Lu to symbolize

in celebration of that

recursiveness.

At work, I watched

wild animal and human student

intelligence unfold, learned what I

could learn about how they learn,

recursively, and helped

students learn

creatively.

For years

and decades after, I

dreamed of a return to the

form and the sculpture, larger

and in a different stone. A version of

Recursion resides in a rock I carved.

In my body and in my mind, over

all that time, it transformed.

Recursively.

Waking

fantasies carving stone,

visions of sculptures, dreams at night.

Families of related forms tumbled in space,

seemingly forever, example after

example of the same

basic thing.

Often, those experiences

brought some new insight about

recursiveness, “out there” in the world and

“in here” , experientially. Nearly always

at those times, I thought of carving

another Recursion.

In late summer

2008, a 5-foot column of red

Persian travertine had been standing

at the corner of my studio for years and I’d seen

it every day. Walking around the corner one day,

I suddenly ‘saw’ myself carving a larger Recursion from

a piece of it. I photographed the original from every

side, enlarged the photographs to the scale

of the column, transferred the outlines

to the travertine, cut off a hunk,

and roughed out the

sculpture.

Roughing out,

I realized that working at

a larger scale, and in a different

stone, brought design options I hadn’t

realized in the smaller, darker,

much earlier sculpture

in serpentine.

I made one small change.

One smoothly curving

surface completely covers Recursion

and it has no edges. Red Recursion has

two smoothly curving surfaces and

an abrupt edge between them.

A protected,

everywhere-concave inner

surface curves itself inward in all

directions, like the inside surfaces of

eggshells. On the other side of an

edge, a smooth, mostly convex

outer surface surrounds,

protecting it.

One surface

became two and evolved:

two surfaces and an edge adjusted

themselves to each other.

Recursively.

While carving

Red Recursion, I was

already imagining exploring

the same basic form in what

remained of the column

of travertine.

After Red Recursion,

I stretched a 3-D computer

model of it it upward and

twisted it around in

various ways to

see how it

looked.

Too much

elongation reduced

the sense of self-reference of

either original and any shorter was,

well, squatty. What emerged was a family

of forms related to my Anima series that evoked

the sense of nurturing that some of them

evoke. Anima II and Heart of Anima

are good examples.

Still in the computer,

I made a mirror-image replica

of the stretched, twisted model, made

large prints of both models, and

used them to rough out two

new sculptures in

travertine.

Both were still

in progress when I first

published this article.

That was the

Grand Plan, at least.

After sitting in the garden for

several years, the two stones parted

company, one eventually becoming

Madonna and Child and the

other Reflections.

Among other

things, these sculptures

embody two ways ideas come to me.

Both are important in sculpting and

elsewhere in my life.

Forms remind me

of thoughts and feelings.

Thoughts and feelings remind

me of forms. Those sources of

ideas are closely linked.

I zoom small

forms up to landscape scale

in my mind and imagine traveling

over them, as if riding a motorcycle at high

speed in mountains. Under these imaginary

conditions, I feel forms kinesthetically in

my body rounding bends. I zoom

landscapes down to sculpture

scale and imagine

carving them.

Here is how I expressed

it on my first

business

card.

“My science

and my sculpting are

about forms and patterns of

objects and events. Ultimately they

are about the ‘shape’ of being alive. Perc-

eption, conception, and expression of pattern

are so deeply fundamental that using them in

any domain promotes their development in all

others. Moving my hands over objects in all

directions is exactly what I must do to

carve them! How wonderful

can that be?”

Wonderful

things can occur

when you pick up a

rock and imagine

carving

it!

Methods of Creation?

tells the Yalakom River Story

from the perspective

of creativity.

During a brief

conversation in Amherst

Massachusetts, I learned of some

amazing research on visualization. A

PhD student and her supervisor devised a

difficult computer-based task that required

quick response and accuracy with a mouse

or some other pointing device. It took a

lot of practice to get good at it. Half

of the subjects practiced daily

and the others on alter-

nate days.

On their

‘days off”, alternate-

day subjects stayed home

and imagined practicing for the

same set time. “What difference did

it make?”, I couldn’t help interrupting.

Practicing half the time and visualizing

practicing the other half was almost as

good as practicing full time. They

also told me some professional

sports teams taught players

similar visualization

techniques.

I never

followed through to

see how it developed, and don’t

even remember their names. But their

story reinforced what I was already doing

in sculpting and encouraged me to increase the

visualization training I was already doing with

students at both graduate and undergraduate

levels. It also encouraged a more imagin-

ative way of writing scientific papers,

especially in the scary parts like

speculating on meaning and

extending theory.

First published in the Vancouver Observer.

Edited February 2021