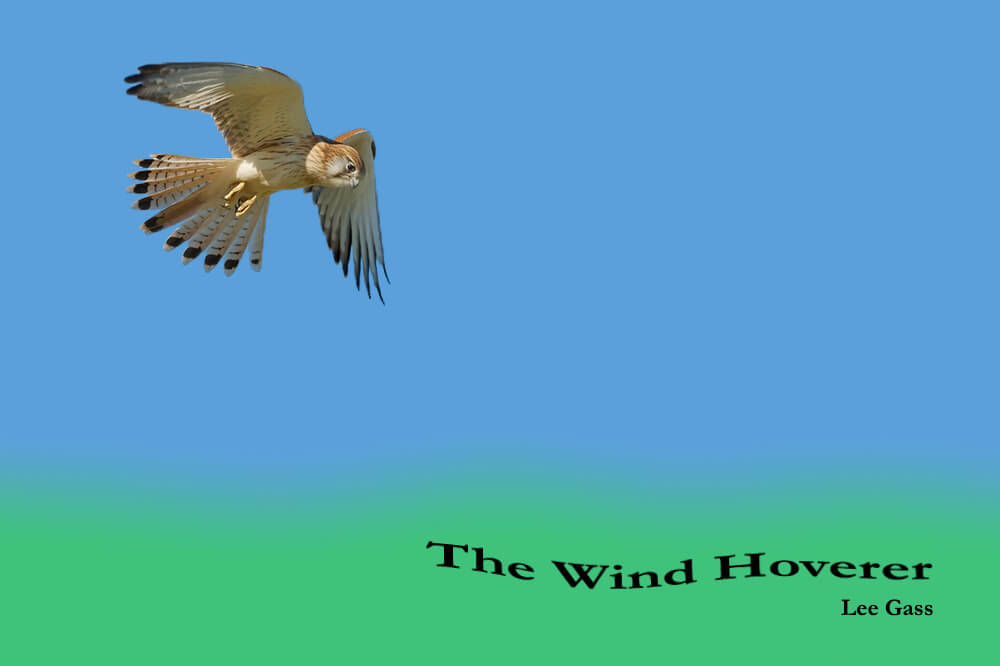

The Wind Hoverer

I was a kestrel,

hovering in the North Sea wind,

inside the last dike in the Netherlands,

looking for voles. If the wind had been calm

or steady that day, finding voles would have

been easy, even if I saw no voles, themselves,

but saw grass wiggle with their passage.

But when is wind calm or steady

inside the last dike?

When don’t grasses wave and sway?

When don’t

dikes buffet, tumble,

and bumble the wind, multi-

plying the difficulty of

hovering in it?

If I attend to

the evidence of my eyes

when grass wiggles in a certain

way, especially if it leaves a certain

wake, I drop and carry

away a meal.

♦

To be

good for running, voles’

trails must be narrow enough to

hide them from kestrels, and wide enough

to let them run freely but not

bump into grass and

wiggle it.

As kestrels

understand the intransitive

verb “to hover”, it is to stay absolutely

stationary aloft, waiting, watching, ready

to drop, despite the roiling wind.

That, precisely, is their

challenge.

♦

When wind moves,

grass moves, and voles might

move along their trails. If I move too,

my own motion is part of my view, and that

makes it much less likely that I will detect them.

When I was young and eager, not yet a hunter

and learning to fly, I bounced, flounced,

and flustered as I flew and I couldn’t

stay still. I rarely caught voles

then, and my parents had

to feed me.

But I

am a wind hoverer

now. I am a killer, calm-eyed,

ready, absolutely steady, and working

like hell to hover in wind.

This story is based on

research by eminent Dutch

biologist Serge Daan. Using high

speed films shot from 2 directions, he

showed that while wind hovering, kestrels

work hard to keep their eyes stationary with

respect to the ground, regardless of wind. They

work so hard that sometimes their heads

are below their bodies, yet their eyes

remain nailed, precisely, to the

center of the earth.

Standing in my

lab with hummingbirds

flying around our heads, Daan

and I speculated about the develop-

mental, psychological, ecological,

and evolutionary significance

of that remarkable

facility.

Using great

poetic license, the scenario

above expresses the most plausible

of the explanations we considered for

kestrels to invest so much life

force in stationary wind

hovering.

For them to

discriminate voles bumping

grass and wind bumping it would be

difficult, even if kestrels were standing

still, and they can do it. But if kestrels’

eyes were moving too, everything in

both eyes’ visual fields

would be moving. Imagine

how much harder it would

be to tell the difference.

what

must happen in perception would be an

inordinately more difficult

problem.

That makes

it easy to appreciate

how hard they worked

to stay still.

Daan’s contribution

to our conversation was his experi-

ence of kestrels and other animals, his long

record of careful measurement of difficult things,

and his desire to explain his new discovery. I had

been reading about signal processing in general,

particularly in the face of noise that can

swamp signals and make them

difficult to detect.

One of my

graduate students was

using the mathematics of complex

wave forms to detect patterns at the time.

I had also been studying the development of

intelligent behaviour in hummingbirds and

human beings (students) at every age

from elementary school children

to life long learners. All

of it helped us think

together.

Like so

many ideas in science,

what we came up with is simple.

Stationary hovering simplifies

kestrels’ view and makes

finding voles easier

in wind.

I don’t know

whether anyone has written

about the problem from that perspective,

but someone probably has. When animals ‘freeze’

in nature, it not only makes them harder to

detect but makes it easier to

detect us if we move.

On the Diaper-changing Behaviour of Robins

and The Deep Meaning of Creativity are

also about adult birds feeding

young who can’t feed

themselves.

A Small

Matter of Maternity

is about species who don’t feed

their young but provide parental care.

Edited March 2021