Sometime in

the late ’70s, MSc student Dave

Marmorek, now Lead Scientist and Director

of ESSA Technologies Ltd, an ecological and social

systems consulting company in Vancouver and Ottawa,

came to me to announce a discovery. His discovery

was not about the lakes he studied, but

about how to study them.

He wanted

to know how lakes “work” as

ecosystems and how lake acidification affects

plankton. He collected many hundreds of samples of

water from a range of depths in a set of

experimental cylinders in a lake

to help him find out.

In one of

many sets of analyses,

Dave compared all those samples

chemically. Crunching that enormous

data set was one way to answer his question.

Each chemical analysis of each sample took

time. Switching from one sample to the

next took time. Organizing and

keeping track of all that

took more.

Everything

took time, so organizing

and managing his

own time had to

be a key.

♥

Before

I tell you about Dave

Marmorek’s discovery, I need

to tell you something about science.

Imagine him doing all that, over and

over and over again, day after day,

working his way through the jars

for the umpteenth time.

Imagine how

boring it

could

be.

I used to tell

undergrads who thought

they wanted to be scientists that

if they didn’t love working out

how not to be bored,

they shouldn’t

try.

They’d hate it, get bored,

make mistakes, and

vanish in black

holes of frus-

tration****

*********

*******

*****

***

*

Maybe

you have to be

nuts to be a scientist, because

‘normal people’ can’t stand doing the

same thing over and over and over

again, precisely the same way,

hundreds or thousands

of times.

As Dave

worked out his time

problem with small changes

in procedures, the work went

faster and more accurately, and

was far more enjoyable. Thou-

sands of scientists make dis-

coveries like that.

My

point here is

that I think what

Dave discovered that

day was how not

to be bored.

They say

“Pile it higher & Deeper”

about the PhD, and there’s a lot of

truth in that. Over and over, and it does

seem endless, we do the same things, as

nearly as we can the same way,

almost ad infinitum.

If we can’t

get computers to do it,

that is. Back then, computers

couldn’t look through microscopes

or analyze samples automatically like

they can now, so Dave did it the only

way there was: painstakingly, by

hand, one after another.

What was Dave’s discovery?

What set the

world on fire for him that day?

What made us glad he discovered it?

What was earth-shaking

about it? Why?

It’s simple.

Dave realized he

didn’t like to be bored

and did something

about it.

By breaking long,

complex tasks into sets of shorter,

simpler ones, he worked faster, got better

data, stayed sharp and attentive,

and had a good time.

They don’t

give Nobel Prizes

for discoveries like that.

But they might give prizes

because of them.

Dave saw that

as something worth cele-

brating and I did too. He made an

assembly line out of his work and manned

all the stations. It was almost as if Dave’s

body was a robot and Dave was

controlling it.

If he did

just one kind of thing at a

time with full attention, his robot

could attend fully to the work and leave Dave

free to reflect, somehow, on other things. Plan

things. Imagine things. Catch errors.

Improve procedures. Other

things.

When Dave

exercised his thinking, imagining,

reflecting self, that made him a creative

scientist. Exercising his robotic self made

him a good technician. Until he was

a good technician, he didn’t have

time to think, imagine,

or reflect.

Escaping boredom

was the key to his discovery.

Here’s what Dave says about it now:

“when I saw each step of the work

as part of a dance, it became fun.

I attended to the thing I was

doing, then danced on

to the next.”

A little later,

Glenn Sutherland had a

similar revelation. He was an MSc

student in my lab at the time, then got a PhD in

advanced mathematical and statistical modeling

of ecosystems, worked at ESSA for years, and is now

with Cortex Ecological Consultants. He is an award-

winning composer of symphonic music. To

celebrate his revelation, Glenn wore a

T-shirt declaring SLAVE! when

he experimented.

According to Glenn,

wearing his Slave shirt when he

did slave work reminded him that he

was both the robot and the scientist, and

both had to do well. Glenn’s cheap trick helped

him make that happen. It sounds kind of schizy

to say it that way, I know. Scientists “should”

be more rational and not have to play tricks

on their own multiple personalities with

T-shirt labels. We all know that

and it’s true.

Scientists like

Dave and Glenn are rational

enough to think up tricks to fool them-

selves into learning action patterns that work

better than the automatic, inefficient, error prone,

unproductive, habitual ones they want to break.

They don’t like boredom, mistakes, or taking

“too long” to do things that “should”

be quick and dirty.

An added

benefit of Glenn’s T-shirt

trick was that every one in the

lab could see whether he was

scientist or a slave at the time

and respond to him accor-

dingly. As a social

signal, it worked.

Early in his

spatial memory experiments,

before he had automated the worst

of the Slave work, he had to do so many

things during one minute out of every

10 minutes for hours at a time, that

no one else could say or do any-

thing to distract him.

But only

if he was his SLAVE

at the time. Otherwise

it didn’t matter.

That is the nature

of experimental science, boring

and repetitive as it is. It is a creative

human venture as well – – exciting and

beautiful to experience when it works

well. What about dance, sculpting,

choreography, or anything else?

One thing I

learned by working in

Experiments, a dance production

expressing the essence of scientific creativity,

is that what I just said about experimental science

applies just as well to dance. I hinted at some of this

in a story about my daughter Susan learning to

dance and our learning to talk about that

over the phone. Here I will flesh out the

idea a little more.

Take

repetition

and precision, for

example. And take

chaos.

Imagine three

dancers rehearsing seriously

for a year, under the guidance of a chore-

ographer and a team of others who know their

stuff. Dramaturge, costume designer, sound, video,

and lighting experts, publicists, scientists to give

feedback and suggest new ideas, and several

investors such as the Government of Canada.

All want a miracle of precision, beauty,

and meaning conveying something

significant about science and

art, and that is a tall

order.

What actually

happens in rehearsal

studios?

You’d have

to ask Gail Lotenberg and the dancers

for the real story. I’m no choreographer or dancer

and haven’t been through this before. But I’ve gone to

rehearsals, talked back and forth on the phone with

Gail, responded to a million emails, and

observed the evolution

of Experiments.

Here are a few things

worth thinking about. It is crystal

clear to me now that when Gail first imagined

Experiments, she didn’t know what she was doing and

knew it. She had good ideas and some survived to the final

production. Most were vague, half-formed, and unworkable

in practice, just as they would be for scientists at that stage.

Ideas evolved as she explored them, and that is also true

of scientists. She tried other things, dancers suggested

changes, or scientists didn’t get it and she returned

to the drawing board. Sometimes we didn’t

get it when Gail didn’t get it and the

production grew richer and

more real as we

worked it

out.

Dance

productions, scientific

experiments, and careers

evolve that way.

Even

the best of us

learn what we are doing,

each time, by doing it. Also like

scientists, dancers improved things

accidentally sometimes by making

mistakes, then the mistakes

became new standards.

Ideas evolve. Possi-

bilities emerge. Things flow

into other things that they

didn’t flow into before.

This happened

for a year in the rehearsal

studio, not that dancers need years

to practice moves. They don’t. But if any-

one suggested something different, Gail

usually considered it, they tried it

the new way, and consi-

dered it some

more.

It astounded

me that they could discuss

specific moves made months or

years earlier and apply them in

new situations. What they needed

the year for, I think, was to ‘get’

what they were doing deeply

enough to do it well.

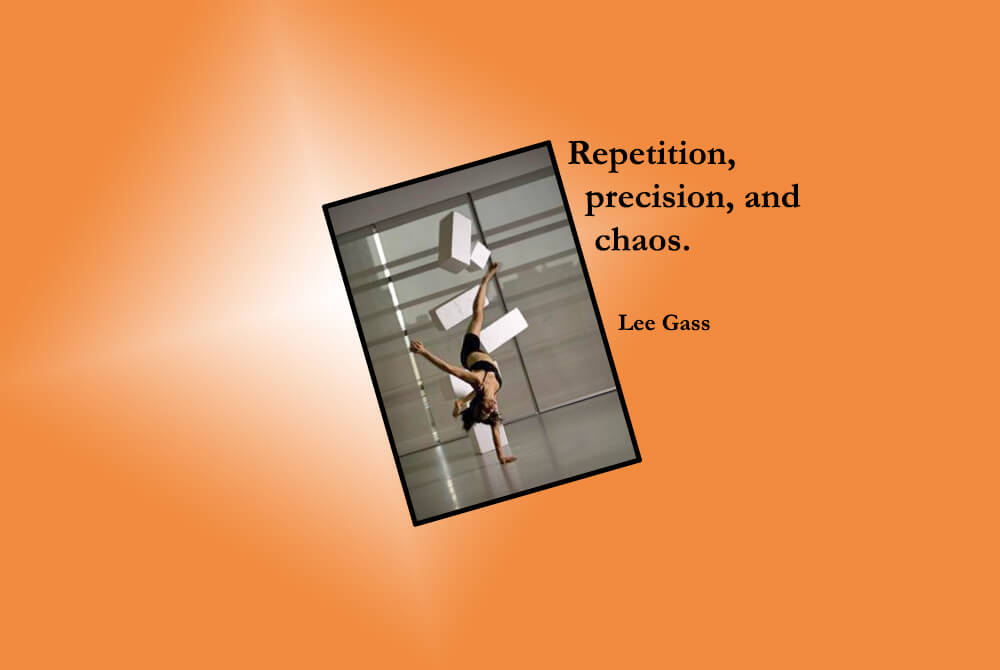

Repetition, precision, and chaos.

The blocks falling in this photo remind me of

unpredictability in the real world: accidents,

lives changing suddenly, new realities,

especially during transitions. Chaos.

That is what the scientists

on the team study in

their work.

Look again at

Darcy McMurray, the dancer

in the photo. Imagine being her in the

studio, live, Vancouver skyline vaguely in

the distance, just before. Then motion, then

blocks falling around you, photographer

shooting photos, hoping for a perfect

shot, just what you’d been

imagining.

But look at the falling blocks.

Back up the tape

to when the motion started.

Imagine motion, collisions, all falling

down. Try to imagine timing, controlling,

or predicting any of it exactly or repeating

any of it, ever, in precisely the same way,

even once in 1000 takes. I don’t think

anything as complex as choreo-

graphy could come out the

same in a lifetime of

trying.

Close, maybe.

But not exactly, and that’s

the way it is in science too. As

hard as we may try, it just isn’t possible

to repeat ourselves exactly, and it

doesn’t really matter in the

long run anyway.

What matters

is not that we behave as robots,

but that we specify accurately enough

what our robotic selves must accomplish, not what

they must do, and make clear to ourselves, first,

what difference it makes that they

stay within bounds we

set for them.

That’s how it

is in science and sculpting, and

something like it is true in choreography

as well. I am beginning to understand that

choreography and rehearsals are conversations

about what might be. They push action toward

limits of human capability, considering how

audiences perceive, understand and re-

member from scene to scene, and

all of it is imaginary until

the premiere.

That particular

conversation must have included

the size and composition of blocks, both of

which determine what it takes to make them fall,

what they do when they collide with each other or

hit the floor, how long they take to rest, etc. It is all

both affected by and affects dancers’ movements.

Little things like that make enormous differ-

ences in what the audience takes

away. And they affect

the photo.

Here is an example

of lengths Gail Lotenberg went

to improve Experiments. At a continent

wide conference of dance professionals, she

staged three performances of one scene, early

in its development, and invited her peers to

comment on it in public (see Liz Lerman).

The professional feedback was deep,

candid, insightful, and figured

in the evolution of the

performance.

Again, my point

is not that I know anything

about dancing, which I don’t. It’s that

I see many parallels between how experiments

evolved and how wild animals, human children and

adults, families, and organizations of various sizes

learn anything. The feedback session with

the pros is what we call peer review in

science. Colleagues tell us what

does and doesn’t work, and

we adjust what we do,

usually for the

better.

A note on Experiments’ subtitle,

“Where logic and emotion collide”.

What a deliciously

ambiguous figure of speech that

is, especially with reference to experimen-

tation! What could Gail have meant by it? She

might have wanted to contrast cool, emotionless,

limitingly logical science with warm, emotional

dance but I don’t think she meant that at all.

My story about Dave Marmorek puts the

lie to that notion anyway. Besides, her

her husband of 18 years is a living,

breathing, Latino behavioural

ecologist, which clinches my

point about emotions.

Here’s what I think.

I think that subtitle

points not to a difference between

science and dance or between science and art

in general, but to a deep similarity. She just said

Experiments was where the collision occurs. Logic

and emotions almost necessarily collide whenever

we commit, without reservation, to learning

anything difficult – it is a Yin and Yang

of experience.

Experiments itself,

i.e. the production, is a difficult

choreographic experiment partly because

the dancing is difficult to perform. More funda-

mentally, it is challenging to communicate the

experience of discovery. To the extent that

it works, it will succeed in conveying

what it is ‘to experiment’.

Dave Marmorek’s book of poetry

Passing Through: Mountain Paintings and Poems,

with painter co-author Dennis Brown,

was published in 2018.

In 2025,

Dave Marmorek was awarded

an honourary Doctor of Science degree

by Simon Fraser University, in recognition

of his decades of global leadership in helping

governments and other entities design

programs to address complex

environmental problems.

This story relates to many others.

Work on the Ugliest Part

addresses the issue in sculpting, and

Frank Spear and the Pea Seeds and Teaching for

Creativity in Teaching & Learning.

The Silver Dollar

has examples from my

first few years of navigating the

world. The story about olives curing

in The Case of Gerald Gass comes to mind

in relation to fine cuisine, and Saw Filer Guy

is a perfect example in industry. As my story

about Gerhard Herzberg makes clear, “if you

know what you’re doing, you’re not doing

science and It’s Not Just a Matter of

Technique addresses the same

set of issues from another

angle in teaching.

First published in the Vancouver Observer.

Edited August 2025