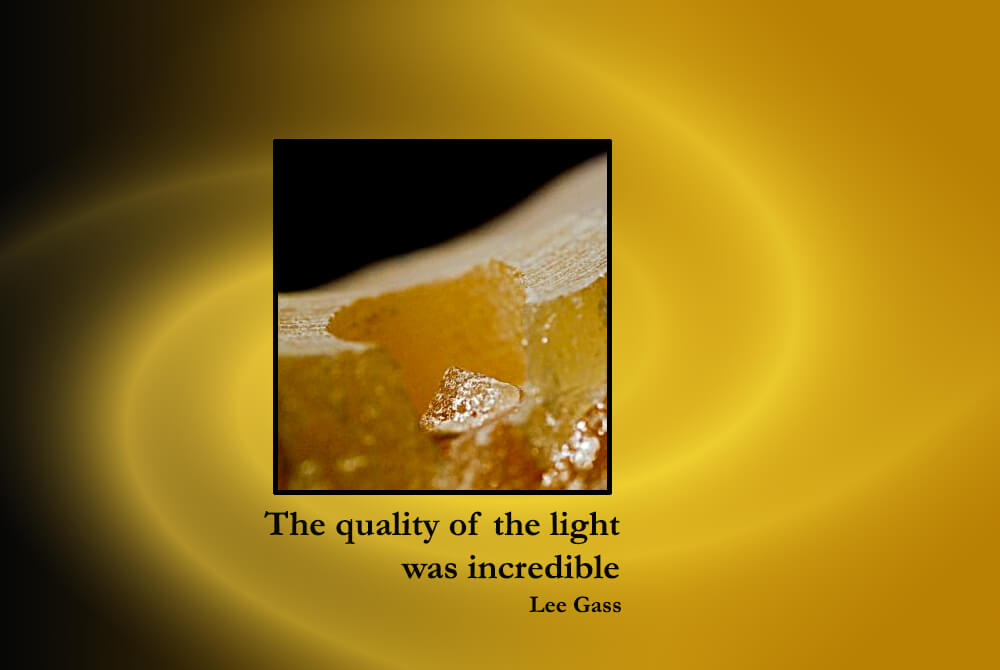

Ode to Joy in progress,

illuminated by winter sunlight.

The Quality of the Light

was Incredible

In the deep dank

dark of a winter in the woods

on an island in the Salish Sea, it poured

all night and blew till the light, and the creek

was high in the day. From the bucking of the

trunks and the roaring on the ridge, we

thought we were in for a long one.

The drumming on the roof

was incessant.

But the quality

of the light was incredible by

afternoon. Sunshine, streaming

to a sculpture I’m carving, angle

low, through winter windows.

No artificial source

can touch it.

Crystals leap to sight,

forms snap to mind, and the colour

of the stone is unbelievable. The quality of

that light is not to be believed, however,

but to be experienced by anyone

who attends to it.

♦

At Grizzly Lake,

sunset was special for us

because of the alpenglow across

the lake. For a few moments at the

end of the day, oranges, pinks, purples,

bright, intense, and fading, domi-

nated our entire world.

Minutes later,

when the sun had gone

and dark was in the hollows,

the sky still glowed the

deep neon blue of

altitude.

Trees stood,

stark in silhouette,

unique as individuals,

each offering sights and

insights less accessible at

other times and places.

I drew trees when I

could barely see

the paper,

Here I was

looking north

from Grizzly

Meadow

at dusk.

♦

Another

special time, especially while

I wore my “scientist’s hat”, was after-

noon in a meadow above camp, facing

east, away from the sun. The meadow

is steep, up to 37 degrees

in places.

Sunset was

around 4 pm in late July,

when meadows on the other side

of the cirque would still be

sunny for hours.

Exactly when

rays parallelled the slope,

skimming the tallest plants, the

entire hummingbird economy we

were studying shifted radically

for a few minutes, trigger-

ed by the quality of

the light.

It was a new

day for a few minutes.

Bright red columbines

popped! against dark back-

grounds, their features vividly stark.

Insects ordinarily invisible stood out

and I could see them well enough to

watch the individuals fly.

In short,

the flying insect

watching was spectacular.

And the best part for me was

that the hummingbirds

could see them

better

too.

That shifted

the balance between nectar

and meat, so they went

for the meat.

From their

perches, hummingbirds

did what I was doing, and their

bill-twitches told me what they

were looking at. Sometimes it

was the same bug I’d been

tracking.

Aerobatically and

aerobically, they ‘hawked’

insects from the air, flitted quickly

from bug to bug to bug to bug, perched

briefly to swallow, then returned to the

air while the light was right.

Meat was cheap

when the light was right

so they went for it. Then

they went back to

nectar.

The name of the game

for the hummingbirds, who were

migrating to Mexico at the time, was to gain

40% of their body weight in fat as fast as they could,

right there in those meadows. As soon as they were

fat enough, they were off on the next 500

or 600 miles of the way to their

wintering grounds.

From dawn until dusk it was

nectar, nectar, nectar for the hummingbirds.

They scratched and scrambled for advantage,

used those advantages as wisely as they

could, and packed away fat

as quickly as they

could.

Being

careful shoppers, though,

they took a bug break

from nectar

at 4.

If they’re smart,

lucky, and female, hummingbirds

may fly from Alaska to Mexico and back

13 or more times in their lives. That’s

a lot of heart beats and wing

beats to fuel!

♦

Imagine early

early morning in the same

steep, east-facing meadow,

where sunrise and sun-

set come early.

Cold air

flows over cold stone

from snowfields above when

hummingbirds arrive. It is

nearly light enough

to see them.

You wear

all your clothes to keep from

shivering. The hummingbirds are

cold too, and wear all their own

clothes – – spherical, feather-

fluffed little butter-

balls.

To pay

for the cost of keeping

themselves warm, they collected

more nectar before the sun came up

than at any other time of day. We could

hardly wait for the sun to come up, and

tracked it slowly down the mountain

toward us, and the humming-

birds tracked it too.

When the very

very tips of the very very tops

of the very tallest trees around us

had the tiniest bit of sun, those hum-

mingbirds were up and outta

there to bask in it.

They left their

perches, left the territories they’d

invested so much time and energy to win,

left the flowers that produced the nectar that

made them fat, abandoned their guardian-

ship of their land, and headed

for the sun.

They spent the

next 10 or 15 minutes

basking, preening, paying no

attention to each other. Drifting

into mininaps, as humans do,

warming and soaking

up sun.

Each morning,

every hummingbird in the

little meadow left for the sun

at the same time, came back

at the same time, and

nobody cheated.

It was

honour among thieves.

Butterballs before,

more like snakes a few minutes later,

warm, ready for the day, and ready to resume

the business of gaining fat for the journey. Nectar

harvest rate dropped immediately when they

didn’t have to eat so much just to keep

warm, let alone gain enough

fat to get to Mexico

on time.

Special light in special

times and places.

Everyone has

heard of the luminous quality

of the light in the south of France. Van

Gogh and his friends made it famous. Painters

like north-facing windows in studios because

of the quality and constancy of their

light throughout the day.

Irving Stone’s

fictional account of Michelangelo

selecting marble at Carrara by the first

rays of sun, said to penetrate to the core of

the block, revealing inner qualities that

otherwise would be invisible. I see

no reason to believe the

myth, but it makes a

good story.

It also

makes a good point

about quality.

In Graphing in

Science and Sculpting I discuss the

value of graphs like this in understanding natural

economies like the early morning one above. That one

graph says everything the story says, except where

they perch, how they get warm, and

where they find their

food.

The hummingbirds in

this story are those I described

in a TV interview as the “Meanest,

Nastiest, Territorial Squabblers

of them all”.

They collude

with each other for a few

minutes in morning and afternoon,

and rufous hummingbirds are definitely not

known for cooperation. Their sunbath is

more like a truce, and it serves them

well to agree on it.

I tell the cold

morning story in the video

Grizzly Lake Story, and relate it

to other hummingbird stories

in A story for Twyla

Bella.

They tell about

the same event, but from

different perspectives and in other

ways, and they emphasize

different things.

Here, the point about

insects in afternoon is that the

quality of light for seeing matters

to hummingbirds. It varies greatly

over the day, and they pay close

attention to it all

day long.

The psychologist

J.J. Gibson would have said

that the quality of the light at that time

of day affords flying-insect-seeing. Other

psychologists say that’s what makes

it clear and salient to them.

Not only

does the quality of light vary

in the real world. So does its quantity.

At the other end of the day, its direct radiant heat

affords geting warm for cold hummingbirds

and I guess Gibon might say that calling

a truce for a few minutes affords

getting warm or getting

flying insects.

Grizzly Lake Story was

part of a full-length dance performance

choreographed by Gail Lotenberg and performed by her

company LinkDance Foundation and developed in collaboration

with four behavioural ecologists. As Gail explains eloquently in

this video, the objective of Experiments was to express

the essence of scientific discovery in dance.

Speaking of hawking

from the air, The Wind Hoverer

is also about that. In that case, the hawks

were in the air, the air was turbulent,

and their prey were hidden

in grass on the

ground.

When I saw my

drawing of trees and sky at dusk in

Grizzly Meadow while editing, it reminded me

of a picture in a publication on an early biological

expedition into the Trinity Alps, I think led by

Joseph Grinnell from Berkeley. It may

have been 1919, which was a

century ago.

In an image of that scene,

taken from near where I drew that drawing,

I compared individual trees with the same trees

in one I took on my first backpacking trip to

Grizzly Lake after 7th grade, 36 years

later and whenever I came

back later.

It would be

interesting to compare

my drawing with a series of

photos of the same skyline

in different years.

Nearly

everyone who hikes up

that trail takes a picture from where

Grinnell took his, so there should be lots

of pictures to compare. The report is in a

publication of the Museum of Vertebrate

Zoology, entitled “Trinity Alps

…..expedition….” or some

thing like that.

Watching

that one skyline change

would be like watching a century-

long clip from a time-lapse movie of the

life of the wilderness and the forest.

It could be an interesting

project.

First published in the Vancouver Observer.

Edited March 2021